The pneumatic tire…remains a product whose characteristics are not easily predictable or comprehensible by conventional engineering techniques.

- From Mechanics of Pneumatic Tires, published by the U.S. Department of Transportation, 1981. Editor: Samuel K. Clark.

The invention of the wheel is often put forward as a pinnacle of human ingenuity, but it strikes me that the defining characteristic of modern transportation systems is not the wheel but the pneumatic tire. In the United States, vehicles with tires carry twice as much freight as vehicles without them. Tires have an outsized role in individual transportation: The vast majority of Americans commute on tires, outweighing all other modes by about fourteen to one. Tires are on our lawnmowers, those iconic symbols of twentieth-century middle-class independence, and they’re on our e-scooters, perhaps the zenith of twenty-first century globalization and consumerism.

The tire’s meteoric rise might have surprised nineteenth-century observers of the wheel, which took millennia to penetrate (and shape) human culture. Wheels emerged in various forms between 3000 and 4000 BCE. Yet even in spite of its obvious utility, wheeled transportation remained expensive, uncomfortable, and relatively rare well into the early modern period. Richard Bulliet writes that as late as 1570, the number of four-wheeled carriages in Britain “could be counted on one hand,” and even in 1814 there was only one carriage for every 145 British inhabitants. By comparison, today Britain has about one car for every 1.6 people – and roughly half of Brits own or have access to a bicycle.

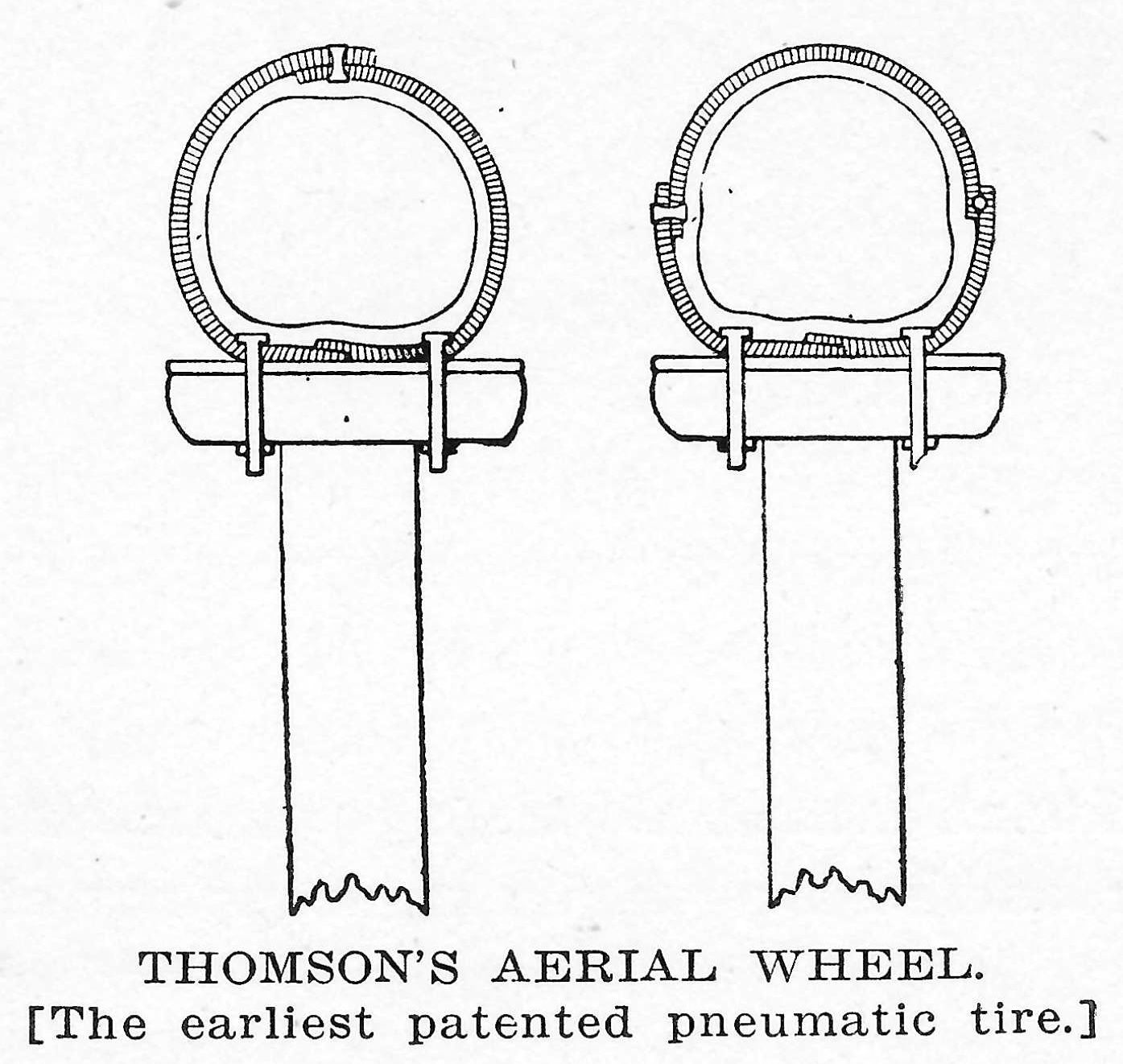

The popularity of bikes, cars, and wheeled transportation generally has much to do with the tire – and the popularity of the tire owes a lot to bikes and cars. In his 1846 patent, Robert Thomson described his “aerial wheel” – the first pneumatic tire – as an “elastic bearing” mounted to a wheel, “rendering their motion easier and diminishing the noise they make.” He wrote this just two years after Charles Goodyear received the patent for his rubber vulcanization process; rubber was, at long last, finally good for making stuff, and Thomson had a prescient understanding of how vulcanized rubber could make wheeled transportation more efficient and comfortable. By far the dominant mode of wheeled transportation of the time was horse-drawn carriages, and Thomson ran a series of tests to understand how a carriage with pneumatic tires would fare. He described in detail how pneumatic tires made travel dramatically more comfortable for passengers, and reduced the total drag on the vehicle by as much as 68%. In time the benefits attributed to tires would multiply: They enable much higher speeds of travel; they improve traction dramatically; they allow a vehicle to maintain traction even when the road surface is uneven; they can greatly reduce the sound of the wheel rolling over the ground.

But Thomson was too early, and his carriage tires had virtually no impact on the course of history: As Henry C. Pearson noted in 1905, “they do not appear to have come into use except as a curiosity.” Thomson himself also seems to have turned his attention to other things; he later moved to Java and invented an improved fountain pen. An incredible technological breakthrough had occurred, but nobody wanted to put pneumatic tires on their carriages.

Forty years passed, with pneumatic tires nowhere to be seen. Solid rubber tires gained some popularity for farm vehicles; Thomson himself patented a solid rubber tire in 1867, six years before he died. But the big thing that changed around that time was the fact that humans began pushing themselves around on wheels – instead of being dragged in carriages by horses.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now