First, a warm welcome to our new sponsor, Onshape, which combines CAD and PDM in one secure cloud platform. We're very glad to have them!

- A smoot is a unit of distance equal to the height of Oliver R. Smoot, who was chairman of ANSI from 2001-2002 and president of ISO subsequently. Smoot had pledged to a fraternity at MIT in the ‘50s, and as part of his induction he and a team of other pledges measured the Harvard Bridge in smoots.

- Re: American flags, which I mentioned here recently, here’s the section of the US Flag Code which concerns flying the flag upside-down. An upside-down flag traditionally indicates “extreme danger to life or property,” though in modern times this is often interpreted metaphorically.

- I enjoyed Ezra Klein’s interview with Brian Eno, in particular this exchange:

Ezra Klein: You draw this distinction when working with generative [AI and other] systems, where you say you don’t want be an architect; you want to be a gardener. What’s the difference?

Brian Eno: The conception of an architect is somebody who thinks about an end result in great detail. The archetype is Frank Lloyd Wright, who designed everything down to the teaspoons in his houses. The whole thing kind of pre-exists in the architect’s mind and then is brought into being by builders.

What a gardener does is put some seeds in the soil and then watch how they develop. “Oh, these ones over here are doing better than those ones over there. So next year I’ll plant them differently.”

You know that if you are making a garden, you are only starting something. One of Stewart Brand’s books, “How Buildings Learn” — it’s a great book [which the SOW Reading Group discussed with Brand in 2022] — in that, he says, you never finish a building. You only start it.

I think that’s what I mean by “generative music." You start the piece, but it finishes itself. It carries on finishing itself for the rest of time.

Planet Money’s Nick Fountain visits a cold storage facility with Nicola Twilley, who the SOW Reading Group chatted about refrigeration with last year. Recently Nick recommended Geoff Dyer’s Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It to me; I enjoyed it. In it, Dyer proposes a “basic rule for the preservation of spectacles: if they’re not on your face, they should be in their case.”

There’s an eyeglass shop, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, called Moscot. They’re an eyewear brand, I suppose, and maybe they’re known outside of the city, but they exist to me mostly as a local business, an institution that tens or maybe hundreds of millions of people would be able to recall as part of the fabric of the city. For a few consecutive years, as I approached my fortieth birthday, I wondered with near-excitement that my vision might be deteriorating, and that I might become a patron of Moscot’s. I saw this as an opportunity, and my physician has repeatedly dashed it by dragging me out to a hallway to take (and ace) casual vision tests. And so Moscot remains an institution that’s a bit out of my reach — a local manufacturer whose products I am sorry to not be in the market for.

But I can dream. Here’s a short video of prescription lenses being ground, polished, and installed in a frame at Moscot’s lens lab. Here’s an even shorter video of prescription sunglass lenses being tinted, after which the Moscot fabrication videos seem to peter out, so I drift instead towards a different channel’s video of a pair of glasses being made from scratch. These glasses are not being made by Moscot, but by Oliver Goldsmith — a person (or maybe a company) that I honestly have not looked into.

But I do know now that Oliver Goldsmith works in cellulose acetate, which I understand as a very popular material for spectacles. Cellulose acetate is made by treating cellulose (a plentiful long-chain carbohydrate, derived from plants) with acetic acid (the acid that characterizes vinegar and which, as I wrote in 2024, “is the result of bacterial fermentation of ethanol”). To make an eyeglass frame, a sheet of acetate is cut to shape with a saw, router, or mill, after which its inside edges are grooved with a grooving bit. Nose pads are added, welded to the frames with acetone; once they’re fully bonded, the frame is finished with files, wire wheels, and a series of abrasive media. Hinges are installed, arms attached, and lenses are popped into place.

For some reason here it’s the acetone that I find myself captivated by. Yes, acetone: Its name, formed from acetum (Latin for “vinegar”) and the suffix -one (the Greek female patronymic, e.g. “daughter of”), means “descendent of vinegar.” This is because acetone used to be produced by distillation of calcium acetate, which itself can be made, as this rather horrible video shows, by mixing eggshells into vinegar. These days, though, acetone is produced via the cumene process, which begins with benzene and propylene, plus a little oxygen and a catalyst. In other words, modern acetone isn’t a descendent of vinegar at all — it’s a descendent of benzene and propylene, both of which are hydrocarbons derived from fossil fuels. It’s just that in the 1830s, some French chemists made acetone out of vinegar.

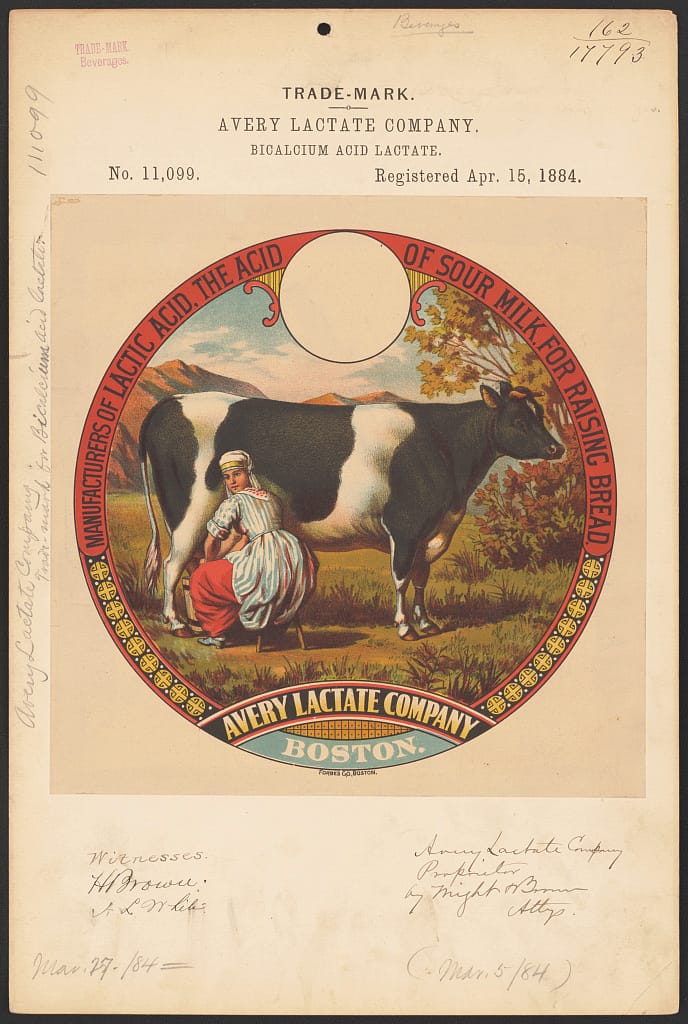

This is the odd thing about the names we use for chemicals: They often become fossil relics, remnants from old and outdated ways of making, antiquated indicators of how one person happened to stumble across a particular substance. Lactic acid, which may be most well-known today for the way it builds up in muscle tissue during anaerobic exercise, was originally named for its occurrence in sour milk. This was in 1780; in 1856 Louis Pasteur figured out that a genus of bacteria, which he dubbed Lactobacillus, was responsible for the production of lactic acid in sour milk. But of course Lactobacillus does not consume only milk (it also thrives, among other environments, in the vaginal tract), and fermentation via Lactobacillus is not the only way to produce lactic acid (our muscles generate lactic acid from pyruvate, which is produced when we metabolize glucose; some industrial processes create lactic acid by reacting hydrogen cyanide and acetaldehyde).

Just as there is no inherent vinegar-ness to acetone, there’s nothing inherently milky about lactic acid; it’s just a chemical compound, C3H6O3, that we happened to discover because we were looking at sour milk.

Here’s a totally unrelated, but funny, thing about the world: You can kind of pick a thing you want to do, document the heck out of it, and make money off of other people’s desire to consume your documentation. Some people might tell you it’s really a funny thing about the current moment; certainly it’s the dream of YouTubers everywhere, but also of certain people throughout history who have written for a living. This past February I biked from my house in Brooklyn to LaGuardia Airport. I locked up my bike next to the entrance to the Marine Air Terminal, then went inside, stopping in at the little shop there for a coconut water or whatever, then sat, in the rotunda, writing about its mural for an hour before riding my bike back home. The ride was a little under an hour each way, and I wrote about a thousand words, including a lengthy description of the mural’s rotunda. Though I never published what I wrote, the whole thing was definitely work — a side quest off of an essay that I did publish. It was a Tuesday afternoon. I had planned different routes for the ride there and the ride home. I considered myself to be on the clock the whole time, but it would also be true to say that I wanted to bike to LaGuardia, and that I had spent the afternoon doing what I wanted to, and documenting it, and at least trying to turn it into work that I’d be paid for.

All of this is to say that I guess I’ve been watching a lot of YouTube, which is to say that I’ve been watching a lot of people documenting stuff that they presumably wanted, for personal reasons, to do. As I write this, I’m watching a British woman named Rosie, living somewhere in Sweden, building what I think (I haven’t been paying close attention) is an outdoor firewood storage shed. She’s built the whole thing using the same set of materials and techniques she used on the shelving unit inside. The tools she uses are ones I myself own, and her techniques are broadly similar to mine as well. But she, like, filmed the whole thing, shot herself lying down in the firewood shed once it was complete, lounging there, sunning her legs. She shows us multiple views of herself doing this, presumably so that we can really see what she looks like there — in the firewood storage area itself, then perched atop its little asphalted roof. The armband of her white tee shirt is cuffed, and I find myself wondering if it was done so intentionally. Her marigold hair is tied into a thick braid. She loads firewood from a hand cart into the shed, then walks away, maybe back to the main house, shot from overhead by drone. I’m transfixed, repulsed, so confused. A scene or two later, Ada remarks at how Rosie (who started the project with “no experience building anything”) seems to have taught herself a lot about construction, and I agree — she’s good. But then there’s a jump cut to a close-up of Rosie pouring herself a cup of coffee from a French Press, and then a shot of her reclining, putting the cup of coffee down onto her newly-built porch, and just basking. I find myself feeling deeply uncomfortable. The video we have been watching has one and a half million views.

“THREE YEARS Transforming a cheap cottage in the Swedish woods alone”. “This is my Favorite Supermarket”. “Sailing and Surfing in Fiji”. You could search for the titles of these videos and see the events and places in them. This may, or may not, give you a better sense of the sensation I want to tell you about.

In many ways it’s the same sensation I get from living in New York City. Shortly after I moved here, in about 2013 or so, I fell into — weaseled my way into, really — a semi-weekly group bike ride. Maybe “group” is generous; often it was just Clay and I who would show up. Mostly we’d ride up the West Side bike path and Riverside Drive to the George Washington Bridge, then up some combination of River Road and 9W to Nyack. It’s a bike route that ranks among my favorite things in all of New York City, mostly because early on Saturday mornings, when we’d ride it, it felt like everyone else who owned a road bike was also doing the same ride. Sometimes we’d end up riding with some of them — fast, in semi-organized pace lines — but we also found ourselves with ample time to chat. We chatted about whether you could 3D print bike parts (this turned into a whole thing) but also about, and here I’m getting back to this sensation, what it means for a place to be a city. Density, we probably started with — you need density. Also a distinct culture, but one with some degree of heterogeneity. You need sports teams (a stand-in for “semi-arbitrary stuff that ties the city together”) and economic magnetism (people who live in other places should see the city as a commercial opportunity) and a regular influx of people moving to the city from elsewhere.

But the definitional urban feature that stuck out to me, and which I’ve been thinking about ever since, is that in cities, people experience big parts of their lives in public. From fundamental life events to basic bodily functions, city life is in many ways defined by the presence total strangers.

It’s a definition of urbanity that I've thought about a lot since. Living in a city entails a renunciation of some degree of privacy. Anyone might see me, and I might see anyone. The other day I directed my eight-year-old to not crash her bike into John Turturro, who was walking home from the farmer’s market with two tote bags full of vegetables. I saw Turturro, and he saw us, and we both also saw lots of other people, hundreds on a single block, thousands on a trip to the farmer’s market. How many people do I see in a year? A million, maybe, equal to a totally manageable 2,740 per day. These people see me sweating, and buying groceries, and searching frantically for a bathroom. They see me furrow my brow at an email I just received, and they see me enjoying a sunny day with my kid, and they see me bleeding from the knee after having been hit by a car. Complete strangers saw me getting married. My first kid spoke her first word while we were out for a walk in the city; surely someone saw me repeating it excitedly afterwards.

If I just looked around me, I could witness dozens of moments like these in a single day. There’s a casual pleasure to this, a warmth that you can experience at any moment. A few days ago I was stopped, on the sidewalk, while my kids fought over who was going to sit where on the cargo bike. A mom walked by with her kid, and I apologized for the sidewalk space we were taking up. She shrugged, waved it off, and then looked back at me as they walked on, giving me a nod and a grin in a way that clearly indicated solidarity and support. I don’t believe I had ever seen this person previously, but for a moment there we both were, witnessing a moment in each other’s lives.

It’s moments like these — chance encounters, often wordless but decidedly social — that draw me to city life. And I think we are drawn to YouTube for similar, but less symmetric, reasons. Rosie shows us her home, and her struggles, and answers audience questions about whether or not she’s lonely. We see unexpected and often unscripted moments in her life; this is a big source of her appeal. But she doesn’t see our lives, and I think that’s a big source of my discomfort. YouTube is dense, and has a distinct yet heterogeneous culture. It’s an economic magnet, and has a regular influx of newcomers, and I would even argue that it has a few semi-arbitrary things that its community members can rally around. But the windows it offers into community members’ lives are one-way only, and it’s makes sense to feel a little uncomfortable about that.

Anyway, a few recent YouTube, and YouTube-related, finds:

- I can’t recommend Listers, a “documentary about birdwatching,” enough. I put “documentary about birdwatching” in scarequotes because we processed it less as informative and more as entertaining; it is a documentary about birdwatching, but it’s also a travelogue, and a character study, and a two-hour-long joke, and honestly kind of a cinematic masterpiece.

- A pretty rad, 65-day outdoor excursion in Greenland, involving thirty kilometers of kayaking, a hundred kilometers of hiking, and an “El Cap-sized first ascent.”

- Tom Vanderbilt writing on Martijn Doolaard, a slow-moving Dutchman who has been working on some seriously aesthetic stone cabins in the Swiss Alps since 2021.

- To me, the ultimate “country living” YouTuber is Liziqi, the Sichuanese vlogger who apparently has the Guinness World Record for “most subscribers for a Chinese language channel on YouTube.” The projects she takes on are epic, yak-shaving sagas, and the experience of watching her videos can feel trance-like in a propagandistic way, but she’s undeniably talented and her wok (seen in this mapo tofu video around 2:30) is a sight to behold.

Thanks so much to Scope of Work's Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks to James, Nick, and Tom for helping lead me to a few of the ideas for this issue.