An Interview with Stewart Brand

A few months ago Stewart Brand, a reader of this newsletter, signed up to become a Member of Scope of Work. Stewart’s work - as a writer, as an initiator, and as an advocate for humanity - is both broad reaching and specific. Best known as the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog (which Steve Jobs famously referred to as “like Google in paperback form”), today Stewart runs the Long Now Foundation, writes, and lives on a converted 1912 tugboat in Sausalito, CA.

Stewart’s 1994 book, How Buildings Learn, considers the arts of habitation and renovation and explores how our physical infrastructure can work with - rather than against - time. The book is a tome, both practical and highly rewarding to read, and we were very happy to have Stewart join us for our final Members’ Reading Group meeting to talk about the book and his career.

Spencer Wright: So, I wanted to start with the ethos that I think that you bring to How Buildings Learn. It strikes me that a lot of How Buildings Learn - and a lot of your broader work - is about the degree to which people consciously and deliberately participate in the design, and the creation, and the maintenance of the world around them. So for instance, towards the end of the book, you advocate living in your own house while it's being built or renovated. Now, I'm somebody who comes from the construction industry, and frankly, I derive a lot of my own self-worth out of the idea that I am handy and that I can countenance those inconveniences. But I also don't know how much to extrapolate from my own experience, right? Like, I'm somebody who's curious about where my sneakers come from and where my iPhone comes from, but I just have to imagine that most people are not quite as nerdy about it as I am. So I wonder: How much do you really think that the society at large should be actively participating in the creation of the world that they inhabit?

Stewart Brand: I guess my answer is: Totally. One of the things I've realized about the nature of the Whole Earth Catalog was that it conferred agency. It gave people a sense that there are always half-open doors that they could peruse and glance through and then maybe walk partway into and then completely dive into the ones that took ahold of them.

When people ask me now, "How about starting the Whole Earth Catalog again?" I say, "It's too late." Because the internet, specifically YouTube, has replaced it, and YouTube confers agency at every level - kids can become world class musicians just by watching other kids who are trying to do that with their glockenspiel or whatever. And repair - everybody can figure out how to repair something. YouTube gets people feeling like they can weigh in on anything - it's just fantastic. In that sense, the early dream that we had about the internet as this thing that would bring all knowledge to all people for free kind of came true. This gets into how information who wants to be free and wants to be expensive. There's lots of stuff that obviously is the wrong information, but I think agency has gone up, and victimhood, which is the opposite, has gone down. And I think you're right, that is sort of my program.

SW: I was looking through a Fall 1969 issue of the Whole Earth Catalog recently, and it's such an interesting time capsule. But it is kind of fundamentally different than the internet, right? It was a curated thing, and there is this trust between the reader and the editorial staff, and in a lot of ways, the reader is outsourcing research and intelligence and wisdom to you as they read The Whole Earth Catalog - which is in some ways, I think, very different from how the internet has proceeded.

SB: No, [Whole Earth Catalog was] classically edited or, as we now say, curated. And you sort of have to buy into the judgment of the curator, and the curator has to be open and diverse and inclusive and all these things, so that the curator establishes they can be trusted. They're not gonna bullshit you, and they're gonna be doing things that they think might be interesting and useful to you. Ultimately, I'm a lifelong editor and curator, and in a sense, what I did with How Buildings Learn was sort of collect everything that I could find in how buildings behave over time and what kind of lessons one might draw from that.

SW: Is there anything that you would do differently about How Buildings Learn if you were doing it again? Or maybe more poignantly, is there anything that you think you got wrong?

SB: One thing I did not catch on to until too late was the importance of landscape architecture, and how it’s treated badly. The architect and developer have various notions and they go ahead and play them out, and then they bring in a landscape architect at the end to dress the whole scene up and fix some of the problems they may have discovered - like huge south-facing windows that overheat the building, so they ask the landscape architect to plant some deciduous trees on the south side. Well, they should have started with the landscape architect who is sensitive to these decisions and knows about wind direction, sun direction, the various regimes of what the rain flow, and probably by now, a landscape architect can face head-on what climate change will bring. That's just not in the book in the way it should have been.

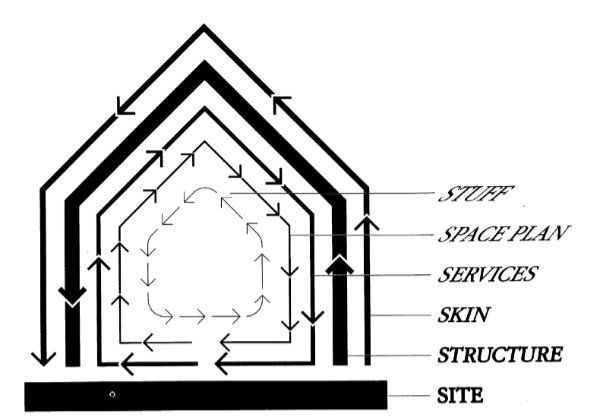

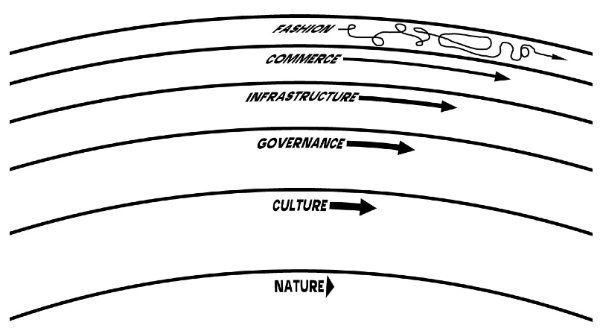

So, I'm going to change the pace layer diagram, which is sort of the fundamental icon and symbol throughout the book. Because I missed landscape architecture, I hadn't noticed how much the view around these buildings changes, often intentionally. And so, I'm adding a scenery layer outside the skin layer. Also, under site, which I treated as quasi-permanent, I want to add another deep layer called nature. These would be the things I mentioned the landscape architect works with - the weather, biology, and biome aspects of where the building is. That is even more significant than the political siting.

Robert Jackson: You mentioned there how the site is only quasi-permanent. I build houses, and the book’s been a big influence on my perspective on building and how I should approach the earth. In our office, we frequently have conversations about climate change, and the eternality of site is in question in a lot of places. So I'm curious, are you optimistic or pessimistic about climate change as a whole - and how do you think climate change affects construction?

SB: I'm pessimistic in the short term, and optimistic in the longer term. I think it's going to take a century, this century, for humanity to get around to doing all that's needed to begin to get ahead of the problem. The sea level's going to keep rising for quite a while now, and already some areas are coming up with workarounds. I live on one - if you have a building that floats, you don't care if the water comes up from time to time.

Some lessons from the book can make up something of a mantra: long life, low energy, loose fit. In this context, a loose fit must include adaptability to variable weather and temperature regimes. Building in both robustness and resilience is called for, and it's going to be completely different in different areas. Hurricanes will be hitting different parts of different coasts. Tornadoes may be hitting in different areas than they used to. So, all of those things are worth bearing in mind for a building that is intended to last a long time.

Climate change has sort of flipped from being invisible to being - to being all we talk about. I think a lot more flexibility is called for, but we’re going to see a certain amount of over-interpretation - people treating anything that happened as, "Oh, that's because of climate change." Well, that may or may not be the case, and so you're going to have to sort out what happens when everything is interpreted through one angle, when there may actually be other angles that are more important.

David Basiji: You mentioned that you were pessimistic in the short term and optimistic in the long term. I would characterize myself as pessimistic in the short term, and, well, not optimistic in the long term. I was wondering if you could give me some hope, and maybe explain your thinking on longer-term optimism?

SB: I'm 83 and counting, and I've seen so many end-of-the-world stories over time - some of which I bought into. I thought that my old teacher, Paul Ehrlich, was right about population, and I did public things in support of his views. He was almost completely upside down, in terms of what at the time was called the “demographic transition.” And then there was the energy crisis, there was peak oil. My environmentalist friends were saying, "The end of the world is coming, not just because of population, but because we're going to run out of oil, and then we'll go crazy." Everyone said that the end of the world was coming, and it didn't. So, I've seen so many ends of the world come and go. I don't believe in them anymore.

The threats often are very clear and the solutions are not - that's understandable because the threat is clear and present! You can usually see a couple of solution paths being offered. Well, the ones that will work, you don't know yet, they're still being invented. This relates to the book Scale, by Geoffrey West, which looks at how cities do everything faster - they create problems faster than anything else in the world, but they create solutions to the problems faster than the problems. And so cities are these places where solutions just pour forth at civilization scale. In the pace layer diagram that I did for civilization, there's a rural version and a city version. The city version of it goes way, way faster - people pay attention to what fashion and commerce are proposing, they occasionally mess with how the governance works, and certainly, infrastructure gets cranked out more rapidly in cities.

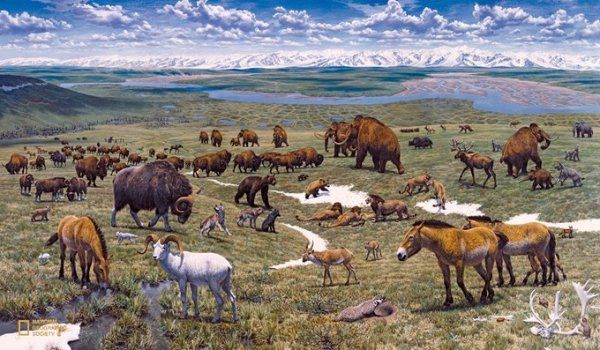

SW: I wonder if you could talk a little bit about your relationship with technology and the balance between technological solutions and cultural solutions. Here I'm thinking about a project that you're closely associated with - Pleistocene Park. While it’s technological at its core, I can wrap my head around it having a really important cultural significance - but I get the sense that a lot of people who consider themselves environmentalists feel a very strong cultural tension with its central plan [which can be summed up crudely as: a) use CRISPR to de-extinct wooly mammoths, b) reintroduce them into a preserve in Siberia, c) restore huge parts of arctic Siberia and North America to grazing megafauna, which d) has the effect of sequestering carbon - and not releasing massive amounts of permafrost-bound methane into the atmosphere].

SB: Well, the climate change angle on Pleistocene Park is sort of an add-on in a way. The fundamental thing is to try to rebuild the Arctic and Subarctic biome of what was called the Mammoth Steppe - it was the largest biome in the world. It actually doesn't require any genetic engineering at all, it just requires lots of Arctic tolerant herbivores. Grazers make grass, and grass makes grazers. And the large grazers are what you need up north, 'cause it's cold and you gotta be big.

Humans largely killed off everything big and the Pleistocene Park vision is if we can kill them off, then we can just as well put them back, so why not? And that would be stabilizing for the climate in the long run. It's increasingly important because the permafrost is no longer perma. It's melting fast and that's leading to a whole lot of greenhouse gases pouring out. It’s a positive feedback cycle where the more they release, the more warming we get so even more methane is released. You're getting fires in Siberia now, and they're producing a lot of carbon dioxide. In response, my wife and I co-founded Revive and Restore, which is bringing biotechnology to wildlife conservation.

My wife, Ryan, got tired of hearing environmentalists saying, "Well, you can't mess with nature like that because nature is very complicated, and therefore you can't deal with the unintended consequences." Hearing about unintended consequences always means “Don't even think of parking here.” It just means go away, stop, forget it, my fears rule. So Ryan put together a conference three years ago called Intended Consequences. We did some research, which it turned out had never been done before, looking broadly at species translocations in conservation. Humans have been doing it for 100 years, restoring beavers to Scotland or wolves to Yellowstone Park. And it turns out that the record is almost perfect! In every case, it did no harm, except for one out of 1000 examples where a local fish got extirpated by accident. In other words, the intended consequences are actually the norm in conservation interventions, and I think we’ll eventually find this with climate as well.

The fact that you don't entirely understand the complex system that you're dealing with should not be a deterrent. I think that intended consequences will become increasingly the norm. And we should build around that.

Thanks to everyone who joined the discussion, and thanks to Stewart Brand for taking the time to chat with us.

To learn more about Stewart’s work, see:

- an upcoming Long Now event (02022-03-22) featuring Stewart in conversation with John Markoff, author of Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand.

- The Maintenance Race, an excerpt from Stewart’s forthcoming book on maintenance, now available on Audible.

- We are as Gods, a film about Stewart's work that covers Pleistocene Park and the Clock of the Long Now in depth

- The BBC miniseries on How Buildings Learn

Starting 2022-02-04, we’re reading Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for our Clean Energy Future by Saul Griffith. Join as a Member today to join the conversation.