The third time I showed up to Micro Center in the hours before it opened, I began to question my own judgement. Building a gaming PC was supposed to be fun. There is a certain thrill in over-researching the benefits of an all-in-one liquid cooler, or the quality of the fitment on a small form factor case. But now, standing in line with a dozen other frustrated builders, there was no fun — only speculation about whether the UPS driver had made a delivery this morning. Like everyone else here, I was desperate to get my hands on a GPU.

Specifically, I was in the market for one of NVIDIA’s elusive 50-series consumer GPUs, which were released on January 31, 2025. Initial online inventories sold out instantly. Micro Center was one of the few physical retailers to receive stock regularly, and there were regular queues at many of its locations. Resale activity was intense, with many cards going on secondary marketplaces for more than double the suggested retail price. I tried using online alert tools, considered deploying my own bots, and joined a Discord to track the latest whispers on inventory levels at my local Micro Center. No luck. It was now mid-March, six weeks after my search began, and the availability was anemic. So I went to Micro Center again.

About 30 minutes before the store opened, a surprisingly genial employee strolled out with a series of paper slips, each one representing a specific NVIDIA GPU. He spoke to each customer in the order they had arrived. If he had a slip for the model you wanted when he reached you, it was your lucky day. On two prior occasions, I had not been so lucky. As I waited for my turn, two questions kept circling around my mind: Why was it so hard to get one of these cards? And why was I even doing this?

A Brief Primer on CPUs and GPUs

To build a gaming rig, or any desktop computer, you need an armful of parts: the motherboard, a few sticks of RAM, a hard disk or solid state drive, the power supply, some cooling equipment, and a case to put everything in. The bulk of a computer’s cost comes from its two processors: the CPU and GPU. As they have such a huge impact on overall performance, this is where builders usually start.

Most of the functionality of a desktop computer comes from the processing capabilities of the CPU, or central processing unit. Its billions of transistors are organized to perform math and logic operations quickly, but serially—one at a time. CPUs are designed to be highly flexible, making calculations that support your operating system, web browser, and spreadsheet programs equally well.

In the early 1990s, a revolution in 3D graphics began with the release of video games like Doom and Quake. In experiences like these, raw geometry data is analyzed in real time and rendered to a 2D screen. There's a ton of math required to figure out what even one demon might look like, given its position, texture, and physical geometry. This presents a huge bottleneck for traditional CPU architectures. Calculating pixel colors one by one is inefficient, and limits things like resolution (the total number of pixels) and performance (frame rate). Gamers traditionally care a lot about these things.

Fortunately, you don’t need to calculate pixel colors one by one. 3D rendering is embarrassingly parallelizable; it can easily be split into smaller tasks, each of which can run simultaneously, since each pixel’s color can be calculated independently of those around it. There was an opportunity to design processors that could leverage this property and free up CPU bandwidth. In 1993, NVIDIA was founded to do just that. Their GeForce 256, released in 1999, was one of the first products to be marketed as a GPU, and it established the company as the leader in hardware-accelerated graphics.

As an aside: The term “GPU” can be a bit misleading. The GeForce 256—and the 50-series card that I was trying to buy at Micro Center—is more accurately described as a “graphics” or “video” card, which has many components. The most important of these is the silicon GPU chip. Modern graphics cards are beefy devices and can measure 30 cm long and weigh several kilograms. Most of their volume (and mass) consists of a sizable radiator and fans for cooling. The GPU itself is roughly the size of a postage stamp and weighs less than a gram. If you’re at all curious about the design and structure of these devices, I highly recommend this accessible deep dive by Branch Education.

By the end of last year, NVIDIA had a dominating 82% of the discrete GPU market. Unfortunately for PC builders like me, they had discovered a much more valuable use for their parallel processors.

A New Market

Beginning in the early 2000s, scientists began to realize that GPUs were useful for things other than computer graphics. They developed open source languages like BrookGPU to hijack the processors and use them to handle intense mathematical simulations, those that could be easily parallelized. NVIDIA took notice, and began developing CUDA (Complete Unified Domain Architecture), a comprehensive set of tools that would allow the parallel processing abilities of its GPUs to be used by the science and research community.

CUDA was first released in 2006, but it garnered little attention until the “big bang” moment of modern artificial intelligence: the release of AlexNet. In 2012, a team from the University of Toronto used two NVIDIA GPUs and its CUDA toolset to build a novel image classifier, which destroyed the competition at the ImageNet Challenge. Their approach showed that GPUs could effectively train convolutional neural networks, a breakthrough that inspired great excitement in the broader tech world. Deep learning algorithms like this could not only be used for image classification, but also things like processing natural language, computing hashes (crypto), and training recommender systems.

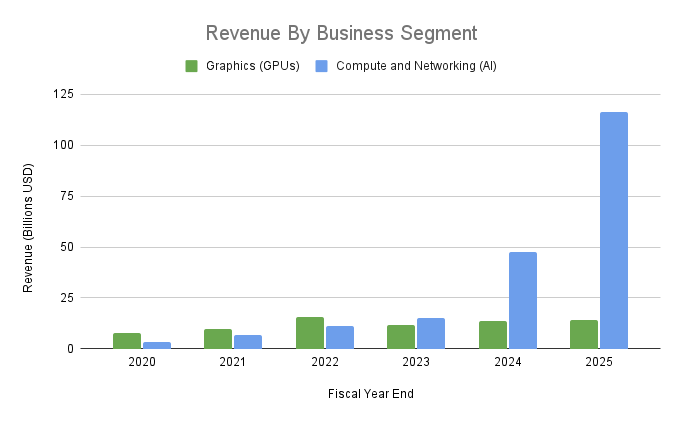

These developments had big effects on NVIDIA’s sales and product development, which became visible when they began to break out AI revenue in their annual reports. They divided the business into two segments: Graphics, which includes traditional GPU sales, and Compute and Networking, which includes data center platforms and other AI systems. I put together a graph that shows the incredible change to their business in a very short time.

NVIDIA’s revenue grew over 1000% in five years, from $11B to $130B. Almost all of this growth came from the AI related segment, Compute and Networking. Graphics, which includes traditional GPUs, went from 70% of their business to 10%. A clear inflection point was the release of ChatGPT at the end of 2022, but the trend was already well underway.

Bad News for Gamers

“Why make cards for gaming systems, when you can sell the same thing to a tech company for so much more?”

This was a common sentiment amongst the PC builders I spoke to while waiting to see if we won the day’s lottery. NVIDIA sells a series of GPUs that is specifically designed to support AI workloads in data centers. They come from the same “Blackwell” architectural family as consumer GPUs. These AI chips are not sold individually, but in custom clusters that come with specialized cooling and linking technologies. Pricing is not published, but industry analysts estimate that the NVL72 cluster, which contains 72 Blackwell AI GPUs, costs about $3M. This means individual GPUs sell to enterprise customers for tens of thousands of dollars. The RTX 5080 I wanted has an MSRP of $999 (though good luck finding one for that price).

Competition with AI customers isn't the only reason why builders can't find GPUs these days. Because NVIDIA is “fabless,” relying on TSMC to actually fabricate their chips, they have to compete with other companies for manufacturing capacity. Making semiconductors is notoriously complex and difficult. The latest GPUs are all made using TSMC's cutting-edge 4 nm process, and it takes months of work across hundreds of highly calibrated machines to produce a single chip. Apple, AMD, and Qualcomm, among others, vie for this limited high-end silicon production capacity. More production is coming on-line, but building fabs takes time. Recently, NVIDIA announced that TSMC’s new facility in Arizona has begun producing 4 nm Blackwell chips. But it would be an understatement to say that supply is constrained.

It would be tough for any company to handle 1000% growth in five years gracefully. When coupled with the competition for fab capacity at TSMC, and the likely differences in revenue per chip for AI and graphics purposes, it’s not surprising that consumer GPU shelves are empty. Demand was always going to be strong, particularly given that NVIDIA had stopped making cards from the prior generation months before the 50-series launched. As a result, older alternatives were just as hard to get and expensive.

Worth It?

My turn in the Micro Center line finally arrived. I blurted out my request for an RTX 5080, and was mildly shocked when the salesman handed me a voucher for one. There was a brief period of elation as I realized that I no longer had to obsessively check online inventory levels at Best Buy or make these morning visits to the store. Before he could change his mind, I redeemed the voucher, made my purchase, and went home to start the build.

I had chosen a small form factor case, and found it reasonably challenging to fit all the components into something roughly the size of a large shoebox. Temperatures and performance are good, so I’m proud of the finished product.

Having completed the project, though, I am not at all sure it was worth it. Thanks to the GPU, I’m able to run the latest games with incredibly high resolutions and frame rates. The ray-traced lighting and reflections in games like Cyberpunk 2077 are stunning. But I’m not certain that I can even perceive the difference between some of the higher settings.

Ultimately, I don’t think I stood in line because of the pretty graphics. Neither did the folks there with me. While we waited, we talked about our builds and the future we might have once they were complete. Some talked about the man cave they were upgrading, others about getting an edge in a competitive game, and a few others wanted to experiment with AI at home. The visions we create of the future can be intoxicating. They draw us in despite their cost. Now that I think about it, this could probably be said of the big AI companies too.

Scope Creep.

- Despite its dominant market position, NVIDIA does have competitors...

Unlike GPUs, Scope of Work doesn’t require standing in line at dawn. But it does depend on reader support. If you appreciate work like this, become a Member or Supporter today.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now