An interview with Virginia Postrel on the history of textiles.

Virginia Postrel’s The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World tells the interwoven stories of textile development throughout human history and into the near future, underscoring just how critical they’ve been to technological development. While synthesizing insights from archeology, genetics, chemistry, and other technical disciplines, the book is anything but dry, replete with surprising details and impressive inventions from every continent.

Virginia recently joined Scope of Work's Members’ reading group for an hour-long conversation about the book. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our discussion.

Hillary Predko: You write about how the success of textiles is a double-edged sword. They're so prolific and abundant today, they’re practically invisible. Also because they're ephemeral, textiles are often absent from fossil records and archeological sites. So we don't always think about how central textiles were to ancient cultures - or our culture today. You actually call it a co-evolution of people in cloth. So what do you think that we gain from being attuned to the really innovative history of textile production?

Virginia Postrel: I'm a big believer in two somewhat contradictory things. One is that it's great to have the luxury of taking abundance for granted - whether that's computer memory, cloth, or food. That's a wonderful advantage we have over our ancestors, it represents a genuine kind of progress.

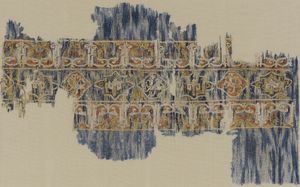

On the other hand, knowing what went into getting us to this point makes you appreciate, first of all, living when you do, but also appreciate how ingenious human beings can be. Even going way, way back there are some phenomenally impressive things, like the fact that people figured out the incredibly complex process of dyeing with indigo all over the world. We have a 6,200 year old piece of indigo cloth from Peru, and people figured it out in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas using different plants that have the same chemical in them. That really makes you appreciate how smart people are - it’s the heritage of humanity that we all enjoy the fruits of.

HP: Throughout the book, you challenge the assumptions of what “natural” means when it comes to textiles. You have an adage, turning Clarke’s phrase on its head: “any sufficiently familiar technology is indistinguishable from nature.” What is the danger of valorizing natural textiles without seeing them as a technology?

VP: I have a lot of opinions about valorizing nature in general, starting with the idea that nature wants to kill you! There are a lot of things to unpack, and one is that the biological textiles that we take for granted, which we call natural, are not natural. It's just that they evolved over such a long period of time for domestic purposes. So something like GMO cotton today is in many ways a continuation of this very long process. It's less of a break than it first appears - it's just that the tools have gotten much greater.

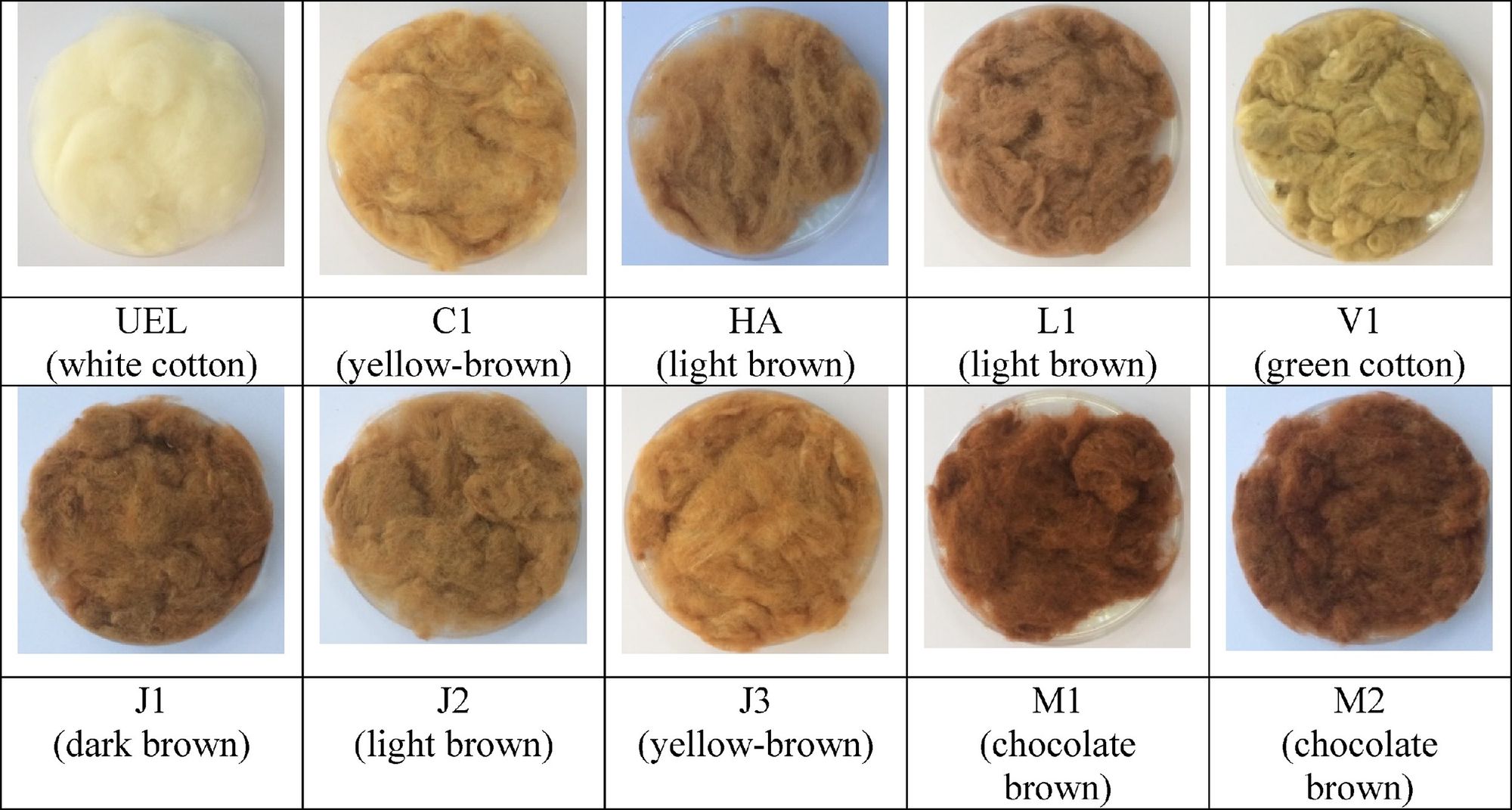

In terms of ancient peoples modifying these plants, it's not just that cotton was domesticated four times in four different places. Once it was domesticated, people kept fooling with it! So, in Latin America, there are cultivated versions of cotton that give you different shades of browns and even grays. The length of the cotton fibers has changed under human cultivation.

Each of these fibers has interesting stories and it puts the need to change plants and animals - to bend them to human use - in a historical context. People have always been doing this, and that doesn't mean it's always good, but the mere fact that it's artificial doesn't make it bad.

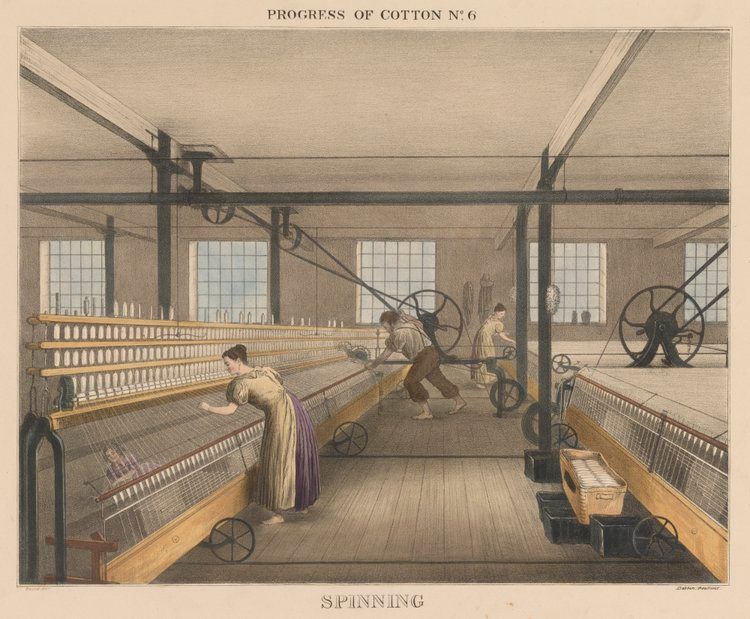

HP: One other thing that really blew my mind was the discussion of how absolutely pervasive spinning was. You call it “less a specific occupation than a universal life skill.” This helped me understand what made textiles ripe for industrialization - the amount of labor involved in making yarn is staggering. And carrying from that, the history of textiles is full of economic upturns driven by automation. I'm curious what you learned about those upturns played out and if there's anything that can help us navigate automation today?

VP: The truth is that the only way to get people to a higher level of material wellbeing is to increase productivity, and that means being able to produce more with fewer inputs. Those inputs can be things like energy or materials, but through a lot of history, it's hours of labor. And so when you get labor-saving automation, and especially when it's not saving a little bit of labor, but it's saving a tremendous amount of labor for the amount of output, then you have a potential for a significant enrichment. And this is what you see with the development of spinning machines, which then made weaving more profitable - suddenly there was no constraint on how much yarn they could get. So weavers had this golden heyday, as Beverly Lemire calls it, for about a generation. Then they faced the other part of the story.

These breakthroughs that increased productivity were good for the world, but not necessarily good for the people who have invested their lives in learning the skills that were intrinsic in the old technology. So you have these very difficult transitions. It was really important that the government in England said to the people who protested spinning machines, then later power looms, "No, we're not going to keep the old technology. We're going to go forward because it's better for everyone." But they could have done more to ease the transition.

When people lose their jobs today, at least in developed countries, they're not in danger of starving. It's bad - and I can say, having been a journalist, this can happen to anyone, it's not just blue collar workers. But I think it's very important to see that as a really important form of progress. Ultimately, it's what leads to higher wages, because, as you know from the book, spinners were paid very, very low wages. There's a feminist critique that says, "See, that's because they were women and people didn't respect their work." But that's really not true, people did respect their work - it was valorized in art and culture - but it took so long to make any useful amount of yarn that the wages were going to be low. And it's only when you have a machine that one woman or even a girl can tend many, many spindles you can have wages that go up.

Aaron Rose: One theme that was really fascinating to me throughout the book was that fast fashion is not a modern phenomenon. People have wanted as much fashion as quickly as it was technically possible throughout human history - with the massive amount of waste it seems to have always produced. Is there any solution to fast fashion, or is this just human nature?

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now