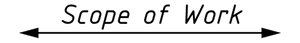

I have a core memory of touring a Phillip Morris cigarette factory when I was a kid. My mom and I rode around the massive plant, thick with the sweet smell of tobacco, on a tram that would not have been out of place at Universal Studios. The factory produced millions and millions of cigarettes daily, combining filters, wrapping paper, and tobacco at unimaginable scale. Strangely, its web of mainframe-looking machines were spread over an expansive parquet floor. Even as an elementary school student, I recall thinking this was a strange architectural detail that didn’t fit with the industrial activity taking place all around me.

I recently asked my mom why she thought the tour was a good idea, especially given that my folks weren’t smokers, and had made it clear that I shouldn't be one either. She told me she had three young children at the time and was looking for some (free) things to do with us. Her thinking was that it was a “cool” thing to see, particularly given the importance of tobacco production to our local economy at the time. I’m glad my mom thought about it this way. It gave me an early appreciation for how things are made at scale. The machines and processes were remarkable, despite what I might think of the industry they were supporting.

Factories attracted tourists almost as soon as there were large factories to visit. Even at the dawn of the industrial revolution in the late 18th century England, textile mills drew visitors from around the world. The mills and their machines were novel to pre-industrial people, and represented a new modernity. In his wonderful history of factories, Behemoth, Joshua Freeman (who the SOW reading group interviewed in 2021) recounts the amazement experienced by early tourists. Unaccustomed to industrial buildings of similar scale, they compared them to “palaces” and their smokestacks to “obelisks.” The near-religious awe was present despite billowing smoke and miserable working conditions.

I can relate to this experience, though I’m from a very different time and place. Factories are rich sensory spaces. The immense scale of the buildings and machinery, combined with curious smells and semi-predictable sounds, can be overwhelming. But a good factory tour, like the one I took with my mom, can take you on a journey from awe to understanding. From the cacophony of sensory input, one can draw out clear inputs, processes, and outputs.

After the invention of the moving assembly line at his Highland Park plant in 1913, Henry Ford began opening his factories to journalists and freely discussing their innovations. The 1915 book Ford Methods and Ford Shops, authored by reporters who had been given access, reveals the extent of Ford’s openness, which was (and still is) fairly novel. Such publicity attracted broad popular interest, and other companies followed suit. Ford not only offered tours of the Highland Park plant, but created several traveling assembly lines for international exhibitions, each of which made functioning vehicles.

The public appetite for industry was strong through much of the 20th century, so much so that the Department of Commerce published several travel guides of available plant tours throughout the United States. The 1962 guide, which you can see here, was beefy, with hundreds of industrial tourism opportunities, ranging from beer brewing to textile manufacturing. The tour of Phillip Morris I took is listed in the even longer 1977 edition, indicating the experience had been available for at least a decade when I took part. These tours did big numbers. My mom and I were among 50,000 annual visitors to the Phillip Morris plant in Richmond. Ford’s River Rouge automobile manufacturing complex drew more than 243,000 people in 1971.

There was a supply side and a demand side to this phenomenon. Businesses had to be willing to allow people inside their facilities. Ford and Phillip Morris believed that exposing current and potential customers to the visceral power of their factory lines might help sell more product. Recent studies back up this intuition: People appreciate a product more if they have some understanding of how it’s made. On the demand side, people are perpetually drawn to the new and the novel. These factory spaces could be as stimulating as a circus, museum, or carnival, and they represented a taste of the future. The factory visit was a serious consideration for those wanting to experience modernity.

My family recently visited the Jelly Belly Factory about an hour north of San Francisco. The tour was a hit with my 9- and 11-year-olds, who are notoriously difficult to please. Jelly Belly’s approach seems consistent with the earlier era of openness, clearly viewing it as an opportunity to boost brand loyalty and spur sales. They have invested heavily in overhead walkways that permit visitors to see the action, videos that explain each step in the process, and an entire museum that documents the 100-year history of the company. They charge a nominal fee for entry ($8 for adults, $4 for kids) and sell special merchandise at the end, but I imagine the company views the experience as more of a marketing expense than a revenue generator.

The 23,000-square-meter facility can produce over 1 million jelly beans per hour at peak production. It was fun to talk with my kids about how its different processes fit together, and to the extent that I was trying to recreate the magic of that cigarette factory tour I took as a kid, their smiles and generally positive reviews were rewarding. I was most taken with the automation on one of the packing lines and a jelly bean tray stacking robot, which you can see in the linked videos. My kids were most taken with the jelly bean samples, which I later found myself feverishly attempting to confiscate from them. This was a surprise: I thought I had avoided the baggage that the tobacco industry brings with it, but had somehow forgotten about the dangers of sugar. Who knows how an industrial candy operation might be viewed in a few decades? Are cancer, obesity, and diabetes really that different?

This gets at some of the moral ambiguity that shows up when you spend time in factories. Where once factories represented a bold future, they now highlight some of the challenges and complexities we face as a society – few of which have easy answers. It is one thing to understand a plant’s inputs and outputs, but now we have to ask questions like, “Were the inputs responsibly sourced?” and “Do the outputs have a negative impact on the environment?” It is fun to marvel at elegant engineering and automation, but such innovation raises questions about potential job losses. While initially in awe of the factory environment, we slide down a gradient to sober reality. Now that we understand how it all works, there is a pull to evaluate it, or (if possible) make it better.

Phillip Morris stopped its factory tour in 1993, implying in public statements that it was a distraction from its “core business” of making cigarettes. But with only 4 of the company's 9,000 employees devoted to the operation at the time, most onlookers viewed it as an attempt to keep a low profile amidst the public’s increasing awareness of the dangers of smoking. While I think their situation was somewhat unique, it is harder and harder to find factories that are willing to share their operations with the outside world.

One reason that companies will often cite as a reason to keep their operations closed is a desire to protect trade secrets and intellectual property. The idea here is that factory processes are developed at great cost, and sharing them freely would give unfair advantages to competitors. I don’t find this reason to be compelling, at least for most operations. Observing a machine gives you scant insight into its mechanical complexity, and the same vendor that makes a machine for one company probably makes similar stuff for their competitors. There’s value in the way the factory itself is run, but one’s ability to protect it (outside of a process patent) is limited given that employees can generally move freely between companies.

Companies also cite safety as a reason for privacy — an argument I find much more persuasive. While injury-free operations are an expectation for modern factory environments, introducing untrained visitors undoubtedly makes things more difficult. If you’re going to have people on a factory floor, they need the same PPE as any member of the team, which is a logistical challenge. The alternative is to build tour-specific infrastructure (like Jelly Belly’s overhead walkways or Phillip Morris trams), but such workarounds are expensive and require long-term planning. Another risk is product contamination, particularly in environments that make food. It would be very bad if an excited child grabbed a handful of jelly beans from one of the big spinning polishing pans that gives the candy its shine.

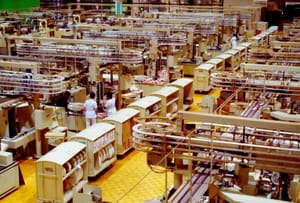

People do all kinds of weird things when they are excited about a cool factory. I, for example, convinced my wife to base our anniversary trip around a visit to one. She finally got me into Bay Center Foods, one of the largest lemon-squeezing operations in the United States. Bay Center, a subsidiary of Chick-fil-A, makes all the juice for the fast food company’s lemonade. I’ve been begging Christina to get me inside the building since her team worked on some of the facility design in 2020. This might be the nerdiest anniversary gift of all time, but considering we met while working on the warehouse floor at McMaster-Carr it kind of makes sense.

I was excited to see the factory because of its scale and the intense level of automation. The 18,000-square-meter facility processes roughly 725,000 kilograms of fruit each day — roughly ten percent of the US’s total lemon production. Bay Center is almost completely automated, with only a handful of employees monitoring operations to ensure things go smoothly. The robots harvest virtually every part of the lemon: The juice and pulp go to Chick-fil-A restaurants, the lemon oils are used by the cosmetics and fragrance industries, and their peels are sold as livestock feed.

The thing that struck me most, aside from the powerful smell of lemons, was the level of preparation I needed to even walk on the floor. After watching a lengthy safety video, I needed to don a hair net, hard hat, lab coat, and steel-toed shoe covers. Only after walking through a dry powder meant to kill listeria, washing my hands, and removing all jewelry was I permitted to see the magic. I had nagged my wife for this opportunity, and it now hit home why it was so challenging to make happen. Food safety concerns alone are a significant barrier to access.

That said, it was one of the coolest plant tours I’ve ever taken. It felt incredibly modern, as humans were only there as stewards for the machines, who took over as soon as the trucks backed the lemons into the dock. We met a few of the employees, most of whom had technical backgrounds in things like mechatronics. This felt like the type of manufacturing we are working so hard to encourage in the US — with high-skill, high-productivity, well-compensated labor. Unfortunately, very few people have a spouse they can beg for access to this vision of the future.

Though factories are less associated with modernity and the cutting edge than they once were, I think this is a perception that is ripe for change. A modern plant is not the dark, dank, and dangerous place of the past. They are often full of creative engineering and automation, the type of imagery many associate with the future. The popularity of shows like How It’s Made (which had 416 episodes over 32 seasons) also reveals that there might be an enduring interest in how we come to have the objects around us.

A bigger challenge is getting manufacturers to allow people in. I’ve documented some of the reasons why businesses might not be convinced that the benefits are worth the costs, but I left out a significant factor that might motivate a change in thinking: talent. Manufacturers often struggle to fill open positions (something I’ve written about in the past), and it is a problem that is only expected to get worse in the future. How can they recruit without leveraging their most dynamic and compelling experience — the high tech factory floor? It is telling that besides the nerdy spouses of Chick-fil-A employees, one of the few groups of people that Bay Center allows into its facility are students from the local school district.

Factories, though complex societal artifacts, have an untapped magic that we should be using to encourage young people to build the future we want. Coming out of college, I had never considered working in an industrial environment. I took the interview at McMaster-Carr because I wanted the interview practice, and thought the trip to Atlanta would be cool. But seeing the facility at work — the miles of conveyor, the meticulously choreographed processes, the thinking put into every piece of the puzzle — made me excited to get involved. Christina and I are not the only people who might also benefit from seeing industry at work.

SCOPE CREEP.

- As factories modernize in China, industrial tourism is becoming increasingly popular. Coveted tours, like the Xiaomi car manufacturing plant in Beijing, receive thousands of applications for only a few spots.

- This 1915 Factory Facts pamphlet was published by Ford to promote its factories and their innovations, more evidence of their attempt to use their operations as a way to sell more cars.

- Though hard to find, some companies do still encourage visitors. This list from Lonely Planet has some pretty good options, including Jelly Belly.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to Christina for always being a good tour partner, and Aaron for helping with some lemon math.

You matter,

James