All good adventure stories contain a moment of real coziness. There has to be a little bit of something homey to illustrate the stakes of the quest, and the reasons for discomfort endured. I’ve recently had the adventure of moving internationally with a nine-month-old baby and enduring the discomfort of paying movers to break a lot of my stuff. Now, domestic calm is what I’m after, come hell or high water.

Domestic life, more than any other sphere, is characterized by its dependence on a personal relationship to a particular building. To live neatly, comfortably, and economically in any place, you have to develop and live out a personal understanding of how that place works. To steal a phrase from a recent journal paper by Bill Bordass, Robyn Pender, Katie Steele, and Amy Graham, you have to learn to sail a building.

To sail one’s home is to embrace an active role as its inhabitant. Architects and engineers provide a seaworthy structure, a building that is legible and intervenable, but its occupants are the ones in charge of sailing it. Bordass et al. focus on heating and cooling, offering a paradigm in which old-fashioned measures and personalized adjustments can be used to achieve a low-carbon, comfortable life. In the architectural world, approaches that seek to minimize the need for mechanical heating and cooling usually fall under the umbrella of “passive design,” and usually prioritize a tight building envelope, extra insulation, and heat recovery systems. But the image of a listless, passive house slouching off into the skyline leaves me cold. Living in a building the way Bordass et al. describe requires a more energetic attitude — at least a little each of knowledge and spirit.

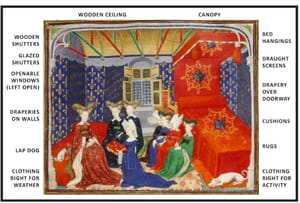

To sail a building implies skill, attunement to environmental conditions, the possibility of adventure. For most of history, living comfortably required an array of adaptive measures. Draperies, tapestries, and rugs were placed between people and cold surfaces to serve as radiant breaks; nightcaps warmed heads and lap dogs warmed laps; and a range of interventions provided localized and personalized thermal comfort, suited to the needs of a particular occupant engaged in a particular activity. And sometimes, people embraced fluctuations in temperature. To a certain degree, it may have kept them healthier. When people live within a narrowly controlled band of temperature variation, becoming “habituated to tightly controlled environments, their thermoregulatory systems begin to shut down,” Bordass et al. note, “making them less able to adapt to changing conditions” and more prone to some modern health issues.

In their workshops with building managers and church volunteers, Bordass and his collaborators taught building occupants some basics of building science and thermal comfort, and gave them access to — and technical support in understanding — environmental monitoring data from their buildings. They encouraged deeper thinking and curiosity about heating, ventilation, and building maintenance, and empowered volunteers to experiment with and implement their own adaptations. Some tried heated cushions for the church pews. Others hung fabric to trap downdraughts from leaky windows. Some invested in infrared cameras, and made use of their revelations.

Sailing a building in this way requires a level of familiarity, understanding, and consistent presence that can be at odds with contemporary Western lifestyles and housing arrangements. It has certainly been at odds with my own haphazard approach to housekeeping and the itinerancy of my early adulthood. As a new parent in a new city, I’m trying to change my ways, and keep house in a manner more conducive to sanity. For inspiration and catharsis, I’ve been reading Home Comforts by Cheryl Mendelson, an 837-page book about housekeeping that is both a compendium of useful household information (“Glossary of Fabric Terms,” “General Guidelines for Good Pantry Storage”) and a spiritual artifact of weight and power. A former professor of philosophy and lawyer who described her passion for housekeeping as her secret life, Mendelson is a firm believer in tuning into the space you live in.

The first chapter of Home Comforts chronicles the different styles of housekeeping practiced by her grandmothers (one Italian, one Anglo-American), and how each emerged from the climates and environs of their heritage. The Anglo-American grandmother kept things tight, dark, and neat, drawing every weapon against chill, rust, and encroachment of the elements. The Italian grandmother, who’d grown up in a hot climate, flung the windows wide. Both of these approaches strike me as examples of sailing a building. Mendelson laments the fact that we seem to have lost some of our ancestors’ practical understanding of how our homes work, and how we might conduct ourselves in them. The magic of good housekeeping, Mendelson wrote, is that through it one identifies oneself with one’s home. The accumulated choices involved in household management come to express far more than just decorative taste. The homemaker’s habits, dimensions, lightness or briskness of touch, preference for warmth or fresh air, and consideration for the members of their household are all embodied in the layout of the home and the ways things are done there.

Where Bordass et al. document the erosion of practical knowledge in the realm of building physics, Mendelson writes about what’s lost when parents decline to invest their children with domestic skills. Both problems have some common cause in the sweeping technological changes that cut across the 20th century. “Every generation makes the mistake of thinking that the next one will repeat its own experience,” Mendelson wrote in 1999:

Many people in my parents’ generation tried to avoid this mistake. They knew their parents were out of date, and they expected to be out of date too. They thought that they had nothing to teach us, their children, about housekeeping because our homes were going to be entirely different from theirs. It is ironic, then, that in trying to be so very modern as to overthrow themselves before we even had a chance to, they made that same old mistake. They had experienced huge changes in housekeeping styles and technologies, but then, unexpectedly, we didn’t. Although homes in 1955 were startlingly different from those of 1915, they would turn out to be remarkably similar to homes in 1995.

The cyclic tumble of the washing machine and the low whoosh of the dishwasher, once new and exciting machines, are sounds I associate with calm and satisfaction — the cleaning is done, or peacefully underway. The whirring crawl of the robovac is still unfamiliar enough that it perks my ears up, but I expect it will take on a soothing power as well (though it doesn’t help that right now my baby is terrified of the little robot, ever since it bumped into her high chair from behind). If the current enthusiasm around household robots is to be believed, we may be on the cusp of another sea change in the world of housekeeping. What will we value, what will we understand, once the next revolution in household technology has come to pass?

One can imagine a possible future in which the robots have gone mainstream and middle-class, where a normal house runs like something haunted by benevolent spirits. The floors are swept and mopped; the dishes washed and replaced in the cabinet; groceries sorted into their respective temperature-conditioned cubbies and preserved with optimal levels of airflow and light exposure; waste and compost and recycling all appropriately spirited away — all by a clockwork of clever and cooperative automations. But one can also easily imagine a nightmare of disconnected blinks and chips from a horde of robots and devices governed by clunky or shadowy apps, harvesting the data of your personal habits and providing only brief and awkward service in return, all incapable of talking to one another or approximating the longevity of a mop.

Already, many technologies crucial to the habitability of our homes have reached levels of complexity that are out of hand for the average maintainer. One memorable essay in my mental file of HVAC essays opens with an anecdote illustrating the trouble that can come when practical knowledge and skill fail to keep pace with technological advancement.

“It just knows.”

The senior HVAC technician I’d been working with on a home remodel answered with the conviction of decades of experience. I, on the other hand, was less certain. How could a new furnace “know” that it had just been connected to a 20-year-old air conditioner (from a competing brand), somehow read that unit’s cooling capacity, and then calibrate its own output to the precisely required airflow? In a bid to reconcile the reading on my manometer with the tech’s supposed savvy, I asked whether he was certain. He was, he told me, quite positive. “Tell you what,” he said. “If I’m wrong, then there’s probably 200 air conditioners in Princeton with bad airflow.”

The technician’s certainty was misplaced. The narrator’s sense that something was amiss was soon confirmed: after a series of HVAC trainings and a few years of projects, he came to conclude “there were probably many more than 200 air conditioners with bad airflow in Princeton.”

Of course, HVAC is not the only trade with dishonest or incompetent actors. Most things don’t work perfectly on their own, and part of using them is becoming resilient to failures that occur, and curious about how to mitigate them. A seaworthy vessel still needs a handy crew.

A building might be flawed in mundane ways, with mismatched HVAC equipment or faulty wiring, or it might embody a mismatch on a deeper level. Take this anecdote from Adam Smith, architect of the Burj Khalifa, as related to Daniel Brook:

“How did the project come to you?” I asked of the Burj, his famed Emerald City in gray scale. I was referring to the design concept but Smith assumed I meant the business proposition. The Dubai developers had approached him, he said, because they admired his design for Tower Palace Three, the seventy-three stories of green-glass luxury that loom over Gangnam, Seoul’s poshest neighborhood. After I clarified my question, Smith explained that the design of the Burj also came from the same building. But the inspiration for that building, he continued, had come from staring out his office window in Chicago at Lake Point Tower, a 1960s high-rise of undulating black curtain wall designed by George Schipporeit and John Heinrich. Completing this architectural series of begats, he noted that Lake Point Tower had been inspired by an unbuilt design Schipporeit’s mentor, Mies van der Rohe, had submitted to a 1921 competition for Berlin’s first skyscraper. This convoluted backstory was, alas, one only architecture obsessives would appreciate so, for the clients, Smith came up with a tall tale. The Burj’s form, he told them, was inspired by a “desert flower.”

The Burj is a facsimile of a facsimile of a facsimile of a building that was never built. In order to sell this facsimile to developers, the architect fabricated a story about its design inspiration. This is all in the past, and what we’re left with now is like no real flower that ever evolved: a glassy spear a half-mile high, disconnected at its root from the vernacular building features (thick walls, shading) that made its local climate livable for millennia prior. Problems stem from this. Building forms and building systems have been copied, lifted and airdropped all over the world, in all kinds of inappropriate settings. The task remains to steward these buildings into the future, using them as best we can to fit current needs and adapting them to suit the world to come. And at the same time, to keep making more, and sailing them all — old and new — over uncertain waters.

It’s possible to prepare for stability, like Cheryl Mendelson’s grandparents’ generation, and be caught off guard by the changes that come. It’s possible to prepare for upheaval, like her parents’ generation, and be surprised by continuity. I want to learn to keep house, and I want to last. I don’t know which lessons I’ll eventually impart to my child, or which she’ll make use of, but I look forward to practicing what I’m learning here: paying attention, making adjustments, tuning into changes in the air.

SCOPE CREEP.

- The staggering numbers of new buildings needed in coming decades are often quoted in multiples of cities we know. Eleven Londons a year for the next twenty-five years, to paraphrase the architect Norman Foster. “One billion new housing units in the next twenty years,” according to writer and theorist Niklas Maak, or “96,000 affordable housing units a day,” if you ask UN-Habitat. But these figures omit more than they reveal. Housing units do not flow undifferentiated from a spout in thousands or millions. There will be no new Londons, because there are no other Londons. No other places where the Thames ebbs and widens in that way, following its course to the North Sea, flowing over that particular history. London today was made by and contains London yesterday. Only a certain type of city, for example, could furnish us with the names and categories of ‘greatcoat’ and ‘raincoat’ buildings—greatcoat buildings being those with solid walls, like old stone and raincoat buildings those with modern, multi-layered construction, which deal with heat and moisture very differently from their heavyweight predecessors.

- My short personal list of top favorite HVAC essays includes, in addition to the one referenced above, Patrick Sisson on air conditioning in public housing in the MIT Technology Review and Salmaan Craig on thermal flow patterns and convective loops for solar heating and natural cooling in e-flux.

- The first author of the “learning to sail a building” paper, Bill Bordass, has an amazing old-school website called Usable Buildings. Push the button in the corner.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible.

Love, Natasha