Standardized units underpin everything in the modern world, and because they just work, we rarely pay them any attention. James Vincent’s Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement from Cubits to Quantum Constants is a love letter to the complexity that unfolds when we shift our attention and truly consider what measurement is. It is an ancient human tool for understanding the world and it continues to be our best way of describing reality. It is the shared language that translates CAD drawings into parts. Measurement is metrology, as in the scientific practice of defining measurements, but it’s also personal and subjective, like our experience of time passing or evaluation metrics in the workplace.

James is a senior reporter for the Verge, the Vox Media site devoted to technology and society. He recently joined Scope of Work's Member reading group for an hour-long conversation about the book and the curious role measurement occupies in our lives. Throughout this conversation, we reference the creation of the metric system during the French Revolution, which is covered at length in James’ book. What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our discussion.

Hillary Predko: The book got me excited about how the invention of new measurements shapes our thinking. It’s part of this broader relationship between taxonomy and cognition, like how cultures that don't differentiate between blue and green don't perceive a difference between blue and green. What's the relationship between how we think about measuring the world and then how we experience the world?

James Vincent: I'm not quite a full Whorf-Sapir hypothesis guy, but I think language and our definitions do shape how we think. They give us affordances in the same way that tools give us affordances. They lead us towards certain actions, and weights and measurements are just part of that. The tricky thing with discussing weights and measures is that they embody a wider sense of quantification, which can be applied very broadly – this idea that the world can be understood better when divided and when quantified and categorized. There was a lot of that in the chapter on medieval measurement, which draws on the great book The Measure of Reality by Alfred Crosby.

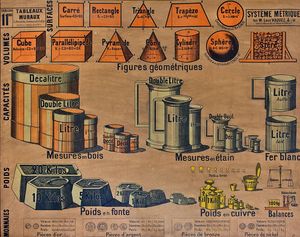

He shows that you can have systems of measurement, which have their practical uses, but you also have just the idea of measurement which is in itself a tool for developing thought. And while there's this general idea of quantification, the specific units and systems of measurement have more of a political focus. Not in terms of policy implementation, but in terms of control of people through the state. With the invention of the metric system, that control becomes a huge ideological campaign. For the French revolutionaries, equality in the law is embodied in metrological terms.

To sum up, measurement as a force is just massive. I barely scratched the surface and really, measurement itself is only part of a broader section of cognitive tools that you might call categorization. Why is something in X-camp rather than Y-camp? Measurement is usually a tool to facilitate that distinction, the categorization in and of itself. You can't perceive the world as one continually connected thing – you need to split it apart, otherwise, you go crazy. Or you achieve enlightenment, depending on which way you approach that question.

Aaron Rose: One thing I love about the book is that the history of measurement could be a history book, like a textbook, but you made it a story, partially through all your field trips. Starting in Egypt, you visited this incredible Nilometer and you visited the original metric standards, which I imagine is not easy to get access to! I'm curious how you picked the sites and what else you would have liked to see.

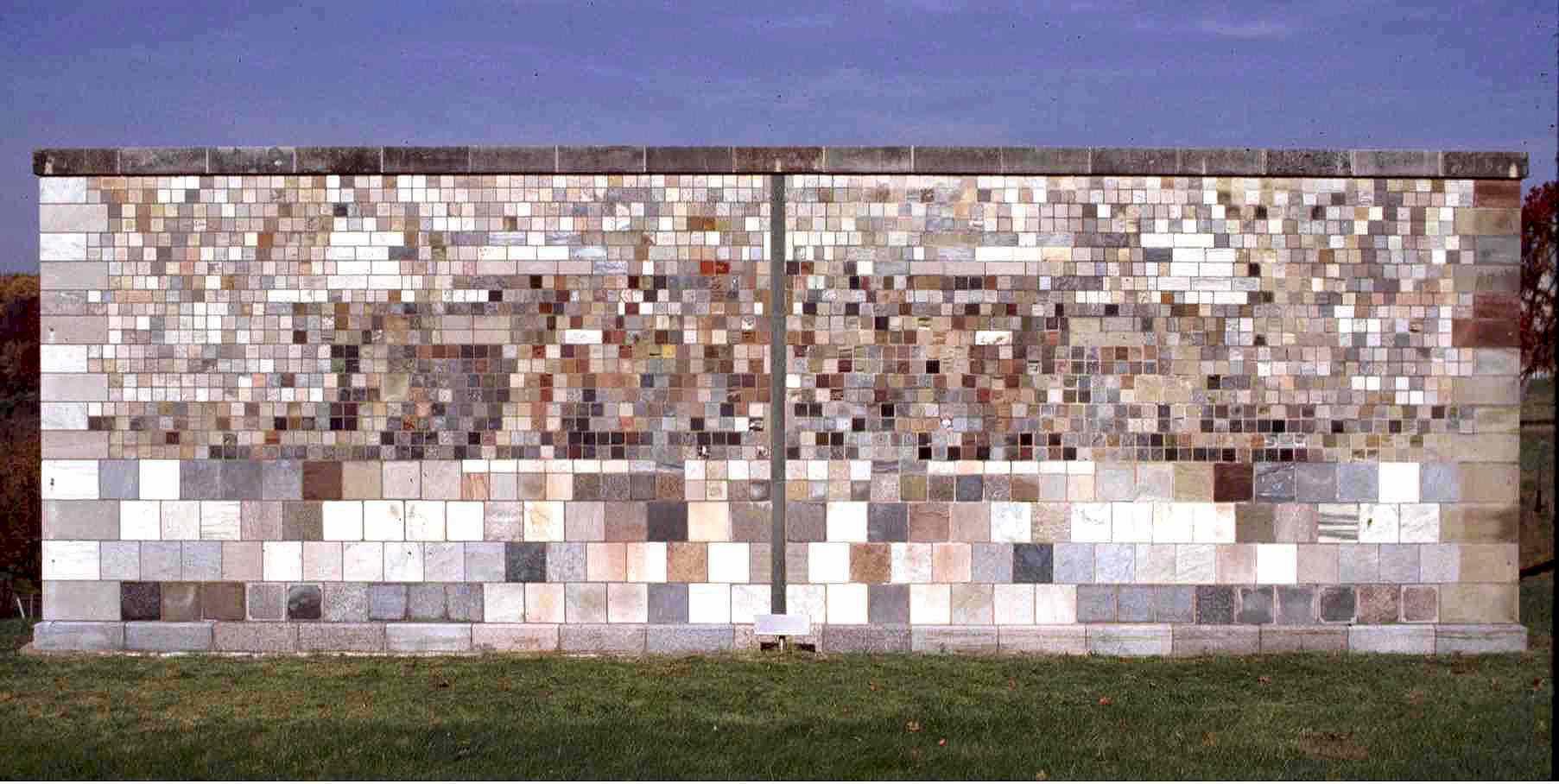

JV: Oh gosh, there's so much. The problem for me was that I wrote most of the book during the UK's [COVID-19] lockdowns. Every time I tried to plan a trip, the UK would institute a new lockdown, or there would be travel bans, especially going to the US. So one place I really wanted to visit was NIST, to see the [standard reference materials] collection in person. The good thing is, if you're curious about that, loads of good YouTubers like Veritasium and Tom Scott have done visits so you can see what it's like. But there was just so much stuff there that I wanted to see there. They have this famous wall in their back garden made up of all their standard testing bricks. It’s this multi-colored wall with different materials and you can see the patterns of where and how they change from limestone to granite.

The Cairo trip was organized in about five days because the UK had just lifted a lockdown and I had two weeks left of my leave before I had to get back to work. I had already been chatting with Salima, the professor of Egyptology at the American University of Cairo, so I just jumped on a plane. There were lots of places I wish I'd got to go to, places like the UK's Center for Physics, and the National Physics Laboratory.

Samantha Luc: As a Canadian, I found the chapter on metric versus imperial fascinating. We just haven’t settled on one system here – it’s all mixed up. We measure weather in Celsius and pool temperature in Fahrenheit. Our stoves are in Fahrenheit but if you get the right or wrong baking book, it could be in Celsius. I worked for a factory that was very insistent on Celsius, so we just had conversion charts everywhere. It doesn't make any sense.

HP: I'm also in Canada, and I've heard it described as the further something is from the state, the more likely we are to measure it in Imperial.

JV: That's such an interesting axis to think about, and it's true in the UK as well. I got into it in the sections where I quote Seeing Like a State, which is another favorite. Standardization tends to be implemented from a top-down level and therefore has to radiate out from these institutions of control. In the UK, for example, there is a personal dimension to the units we use that are non-metric. It is pints in the pub and pints of milk. It is your weight and your height – we talk about feet and inches and pounds, ounces and stones.

It's funny, they weigh babies in the UK in metric, and they always tell the parents in Imperial. So there are two units used: one is for the official government log, and the other is for: "This is how you relate to your baby and understand its size." It has to be translated. And I just think that's such a lovely encapsulation of that translation, and as you said, that sense of distance from the state.

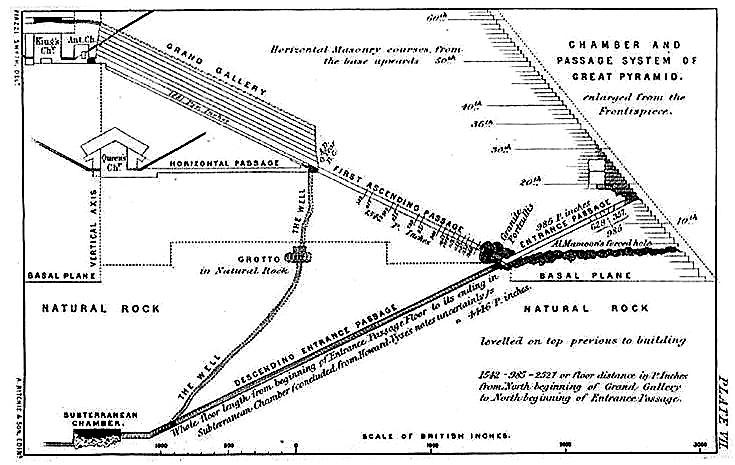

HP: I knew there's tension between Imperial and metric measurements but your chapter goes so much deeper than I could have imagined. The Tower of Babel is held up as this example of what metric is aiming for. But the pyramid conspiracy theory really got me. Could you talk a bit more about divine geometry and pyramidology and how they’re used to support Imperial measurement?

JV: Honestly was a surprise to me as well. You mentioned the Tower of Babel and that conversation came up when I met with the head of the Active Resistance to Metrication. He, as a devout Christian, saw that God cast the world into different nations therefore we need to maintain different cultural systems. But pyramidology was what really surprised me as well.

Of course, I'd heard about pyramidology, this idea that there's some other mystical aspect to the pyramids in Egypt – it's something we now see as part of the ancient aliens-style conspiracy theory. However, it literally comes out of metrology. Simon Schaffer, who is this incredible scholar in the UK, who does a lot on the history of science, history, and philosophy of science (and is one of my intellectual inspirations) has written about it, so I got into it from his work.

The Napoleonic campaigns in Egypt involved a lot of measurement, and that is where the West gets the first accurate measurements of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Basically, they decide that the pyramid was measured out in this unit they call pyramid inches which happens to be pretty much the same as the British Imperial inch, and they conclude that it is the same inch that was handed down by God, which was meant to be contained, encoded in the pyramids for all time, for all generations, and therefore to move away from the British Imperial system is to flout God's expressed wishes.

So, the real seed of that conspiracy theory comes from the use of measurement as a form of control. And I find it interesting because it's almost as if you have these people who are looking to control these objects, and they do that by measuring them – they get so intoxicated with the measures that they've created, that it spins out of their control. They think there must be more to it than this; these numbers must mean more than what they are. They've measured the pyramid, they've gone all over it, but they don't know it any better. They don't know it culturally, they don't know the actual significance of it.

To understand that would take actually listening to Egyptians about their history and talking to them about it to find out what the significance is. Instead of that, they look for the significance in what they know and can control, which are the numbers. And therefore you have to derive significance from those numbers. And I think that is why measurement only will only get you so far – you need other disciplines, like the soft social sciences, because you need a synthesis of those two approaches to understand the subject better.

Spencer Wright: I'm curious what you think the long-term implications of these systems are. Presumably, there are actual long-term societal effects from the way that we measure things. There are significant differences between Imperial and metric, and there are benefits to each one. But the metric system is based on a flawed understanding of the geometry of the Earth – does that matter? After having looked at these systems and their impacts, what do you think the effect is?

JV: I think my conclusion is that anything that builds consensus, anything that allows communication, is worth it. That justification for Imperial units, that it’s more useful to have easy divisions into quarters, thirds, and halves, definitely held up at a time when we were buying more loose goods – I think it genuinely reflected how measurement was used. And now when everything is pre-packaged, those calculations are less likely to be used. Of course, there are professions like woodworking, where being able to quickly half, third, and quarter continues to be useful.

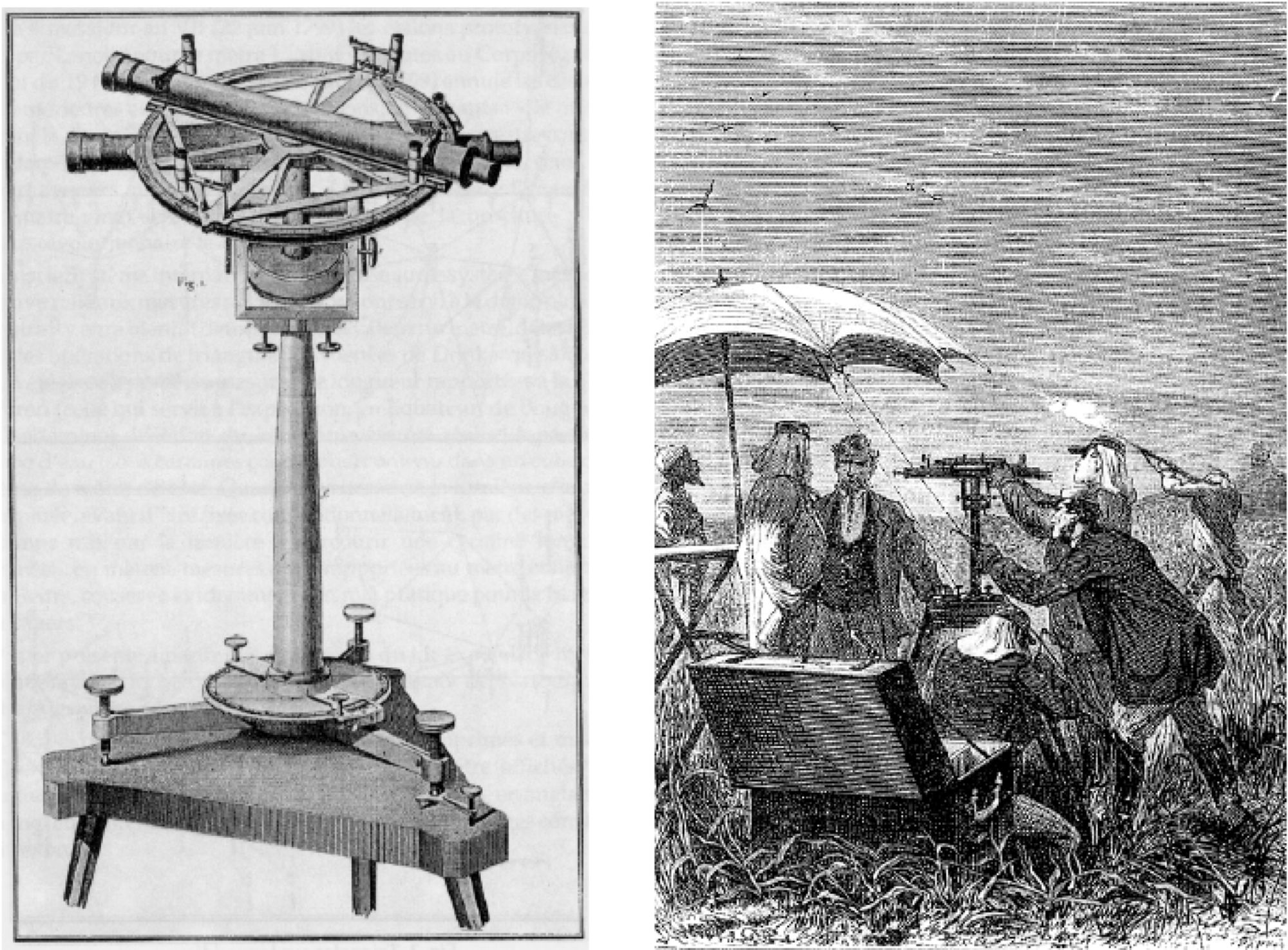

You mentioned the fact that the metric system is built on an error, and it's built on two, really. The first is in the actual measurement. To derive the meter two astronomers, Delambre and Méchain, set off from Paris in opposite directions to calculate the meridian of the earth. Méchain made a calculation error during his journey that just got covered up. The other is the fact that they got the actual length of the Earth wrong because it is not this uniform sphere. But it doesn't matter! The thing I say in the book is that the fact that there are errors doesn't matter in the slightest. What mattered was the story that the French scientists and politicians were able to tell, which was a story of adversity, great intelligence, and hard work. That helped sell people on the metric system and its purported neutrality.

So I think, yes, different systems of measurement do have effects on how we interact with the world. But the greater purpose of measurement itself is as a tool of communication. Measurement is a language that affords communication at a distance – that's much more important than any individual artifact of the measuring system.

Thanks to James for joining us, and to Scope of Work’s Members for your questions. An excerpt of Beyond Measure is available in The Guardian and as a podcast, but I really recommend reading the whole book.