It is a time for reflection. The second-to-last Monday in December may as well be the last Monday in December, depending on holiday observances and one’s tendency to coast through this last week. If you’re one to assess the year that’s nearly passed, you really ought to have started by now. For my part I did recently look at my beginning-of-year goals, of which maybe three-fifths have been checked off, and I’ve been thinking about the non-goal achievements I’ve both made and missed. When thinking about those gets to be a bit too much, I turn to making lists of excellent bike rides ridden, and impressive home projects completed, and (our topic for today) mind-focusing books read.

Looking for something good to start reading in 2026? Try Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress, by Hasok Chang, which the SOW Members’ Reading Group (which you should join!) will begin discussing on Thursday, 2026-01-08.

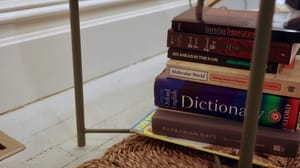

Barbarian Days by William Finnegan

More than anything else I consumed this year, Barbarian Days infected my mood, my outlook, and my sense of my own life arc. I listened to it, on audio, at least three or four times back-to-back, and then I bought a paper copy so that I could study a few key passages. I was deeply affected by Finnegan’s stories, which are nominally about surfing but are really about a life fully lived (and fully reflected upon). Finnegan paints himself as a rich, nuanced, and ultimately flawed person, and the net effect is that he feels genuine, vulnerable, and trustworthy. This is great — anyone who writes a memoir would want to be trustworthy — but the real payoff is when Finnegan then leverages the readers’ trust to describe his closest friends and family members with tenderness, generosity, and grace. Throughout the book, his level of emotional availability is staggering, and the fact that it was counterbalanced by Finnegan’s truly jaw-dropping surf sagas made the entire package a blast to read. I was left with the sense that Finnegan was both larger than life and also deeply human; he’s not a hero, but he’s an incredibly effective protagonist. As a writer, I found this inspirational, and it reinforced my sense that my own emotional availability might enhance whatever other story I want to tell — whether it be technical, historical, or simply explanatory.

Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

Four Thousand Weeks, along with Meditations for Mortals, had a big effect on the way I thought about my own ambitions and life outlook this year. Burkeman begins from the realization that there’s effectively zero chance that his own achievements will be remembered past his own lifespan. Almost nobody leaves a legacy that outlives them, and it’s not immediately clear that doing so is even a good or admirable thing. We all die — our lives last roughly four thousand weeks — and so maybe all we can do is try to use those four thousand weeks as best we can.

This all may seem banal, but I submit to you that it’s profound. Burkeman is not defeatist, and in fact he retains quite a bit of optimism while writing about his ultimate demise. But his practical approach towards his own life “accomplishments” (or lack thereof) is refreshing, and the way he communicates his life philosophy is energizing and enduring.

Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino

I was surprised and impressed with the way that Tolentino blended erudite and vaguely academic criticism with her own intimate and rather rambunctious personal history. At times her cultural, art-historical analysis verged far beyond my own interests, but Tolentino is such an interesting and appealing person that I stuck with her. Even more so, I found myself racing, dragging my own jaw across the floor as I tried to keep up with her, craning my neck to get a better view of whatever she was looking at, trying in vain to recognize her in the crowd around me. The book made me want to listen to Tolentino, whatever she was writing about.

Trick Mirror is itself a set of essays, each exploring some intersection between modern culture and self-identity. I’m not sure whether it affected how I understand my own self-identity vis a vis the culture in which I live, but it did convince me that these two things can coexist in a single text, and that that text can be both serious and fun, reflective and speculative, broad and specific. These were, I think, important lessons for me to be exposed to, and I’m glad that Tolentino put so much of her intelligence, experience, and wit into them.

All Fours by Miranda July

For the past couple of years my wife has joked that I’ve been experiencing some kind of midlife crisis, and inasmuch as I’m in the middle of my life I’m inclined to agree with her. Having already read some of the most well-regarded twentieth-century midlife crisis books, and being aware that the lion’s share of my social circle had all read All Fours, and being a fan of Miranda July’s film work, I finally decided to listen to it while undertaking an extensive backyard project early this summer. It did not disappoint; in fact it transfixed me. July’s approach towards even the simplest problem feels both naturalistic and utterly bizarre, and it was both fun and vaguely enlightening to track her reactions to a pretty traumatic series of midlife events. In one sense her idiosyncrasies (and the extreme nature of her midlife traumas) made the book difficult to relate to, but at the same time her way of explaining herself is so completely logical and well-reasoned that it’s impossible not to empathize. My biggest takeaway, though, is that life is hard for all of us — no matter what stage you’re in, and no matter whether you share July’s (let’s say) atypical way of dealing with life’s difficulties.

QED by Richard Feynman

If there’s one thing I’m really into, it’s soulful descriptions of highly technical subject matter. There are many lanes within this particular pool, and Feynman, with his jocular, winking style occupies — one might say defines — one of them. This book, which attempts to explain how photons and electrons interact (and how their interactions go on to explain many of the phenomena we can perceive, from the partial reflection produced by a piece of glass to the difference between conventional and nuclear explosives), does not always manage to balance explanation and entertainment, but in its best moments (which in my opinion occur towards the end of the first chapter) it is brilliant. Like any good physics text, I would be best demurring if asked to explain its contents. But QED (which was originally written as a series of “lay” lectures, and includes many beautiful diagrams) was both enlightening and fun to read, and more than anything it seemed to be driven by Feynman’s genuine (and infectious) pleasure in attempting to understand the world around him.

Thanks as always to SOW’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks especially to the SOW Members’ Reading Group, who together do wonders in helping me focus on thought-provoking texts.