During the Sydney leg of her Eras Tour, Taylor Swift sat down to the famous floral-painted upright piano that featured in the solo “acoustic” segment of her show, only for a layered string sound to unexpectedly come out when she hit the keys. This glitch – which some fans hypothesise was an easter egg rather than an actual technical mishap – was promptly fixed by a black-clad technician. When Taylor resumed playing, the sound was a rich and familiar piano tone, connoting analog authenticity but clearly just as synthetic as the strings.

There are lots of reasons musicians may choose to use an electric piano on stage rather than an analog one. Pianos are famously finicky — an awkward combination of large and heavy yet internally delicate. They also need the kind of tuning and calibration that is challenging to coordinate in a machine as big and rapidly-moving as the Eras Tour. A digital piano, in contrast, is reliable, fits seamlessly into the tour mechanics and is easy to integrate into the show’s sound system without external mics.

In her banter, Taylor didn’t hide the fact she was playing a digital instrument. But the compact wooden structure of her piano — a housing originally designed for an array of strings and hammers — looked like something that would be more at home in a community hall. Seated behind the painted piano, Taylor was able to communicate a sense of shared intimacy, musical history, and connection to craft. Sure, the Accor Stadium is a vast arena full of 60,000 people, but in that moment you could imagine she was playing a low-key show just for a few friends.

An instrument is an implement for carrying out work. Etymologically, instrument comes from the Latin īnstruō (“build, construct; arrange”), reflecting their role in the construction and arrangement of our human-made environment. A musical instrument produces sound; a flight instrument measures the speed, altitude, and flight angles of an aircraft; a surgical instrument allows doctors to do things that would be impossible with hands alone. To use an instrument is to build a world. Over time, the tool or instrument comes to tell a story in itself — a story about the culture and material conditions out of which it emerged.

In this way, the fake instrument also tells a story. In Taylor’s case, a keyboard perched on a folding stand just wouldn’t have the same narrative heft as the handpainted upright. Removed from its original context of the community hall or bourgeois living room, and relieved of its original strings and hammers, the wooden piano can still be called upon to tell a story about music history and craftsmanship. And if there’s one thing you can say about Taylor as a touring musician, it’s that she is a master of storytelling and world-building, every prop and outfit change contributing to the richly textured narrative.

Elsewhere in the same concert, Taylor played a moss-covered grand (digital) piano to accompany her set from the “Evermore” era, bringing the cultural caché and serious concert hall connotations of the grand piano to bear on what was otherwise a moment of forest-nymph whimsy. This nimble playfulness — pianos that are real but fake, sound that fluctuates between analog and digital, encoded messages delivered with a nod and a wink — reflect the many functions an instrument can serve, and the many modes it can toggle between. Instrument as tool, instrument as story, instrument as decoder ring. Perhaps there is no such thing as a fake instrument.

What becomes of an instrument whose function has been forgotten? It might show up on Reddit’s r/whatisthisthing, where people post mysterious objects and ask for input from the commentariat of historians, material culture experts, and random shitposters. What is this thing? Oh, it’s a cannonball. What is this thing? Oh, it’s a stick of radioactive thorium (update: the bomb disposal unit is on the way). In aggregate, r/whatisthisthing is a poignant reminder that instruments are nothing without their cultural and historic context. An inscrutable “paintball like sphere filled with glue” turns out to be a bath bead, that omnipresent slippery scourge of many 90s bathrooms. Like they say, the past is a foreign country.

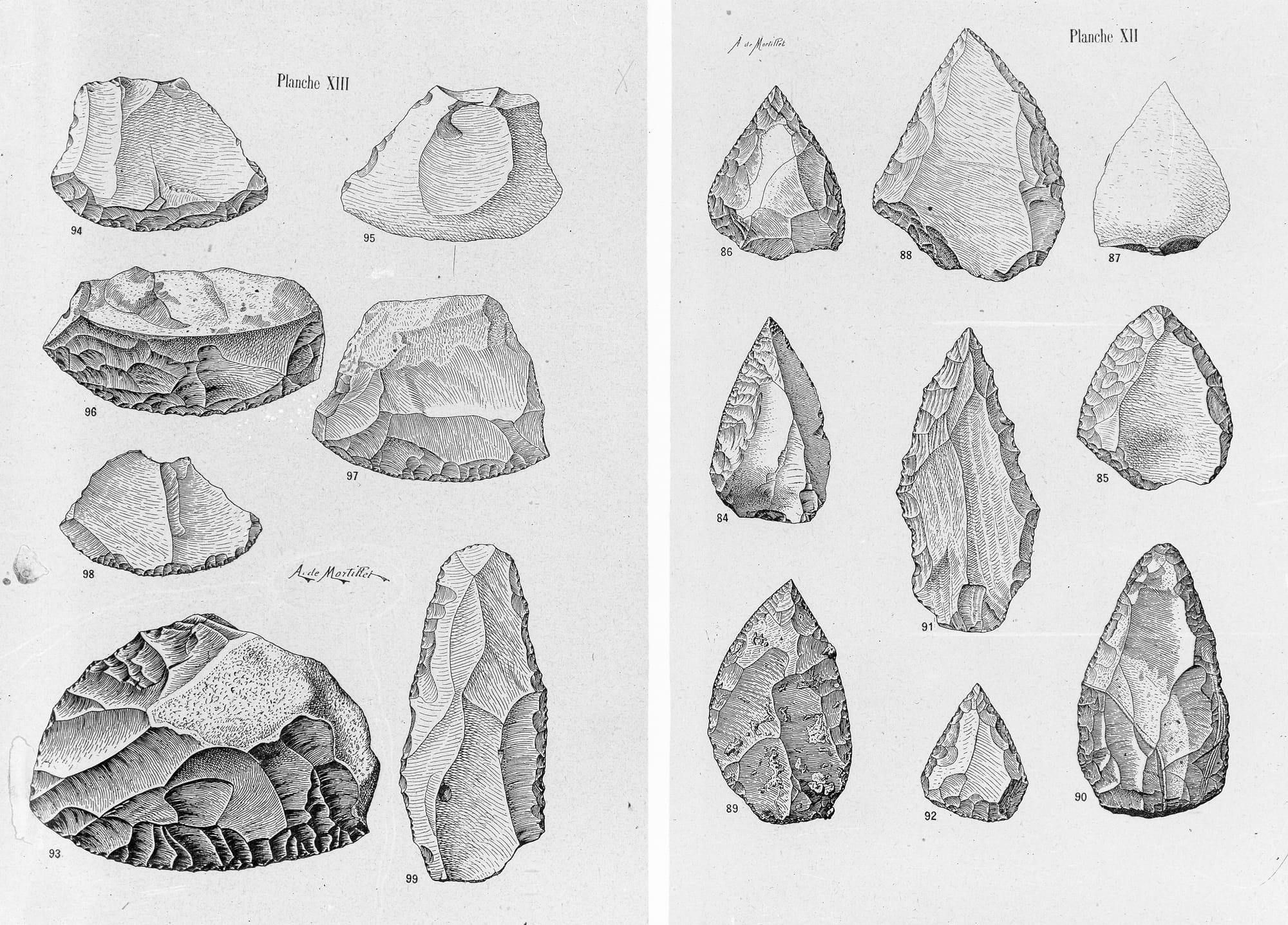

A world away from the crowdsourced investigations of Reddit, archeologists have a whole discipline’s worth of techniques for figuring out how ancient tools were used. Use-wear (and micro-wear) analysis is one form of lithic analysis that involves closely examining the working surfaces of lithic (stone) tools to identify their likely function. The traces of wear tell a story that analysts attempt to read: was this stone shard used to scrape, cut, or pierce? But even the most careful examination of an artifact can’t address every question a researcher might have. To test hypotheses about object use within a particular culture, the sub-field of experimental archeology offers a different approach. Experimental archeology is something like a LARP — practitioners try to replicate tools or structures using historical materials and methods, then use them to perform tasks (like hunting or cooking or fighting) to understand their function and the skills involved. If a tool can tell us something about the material culture and social environment out of which it emerged, then experimental archeology posits that this knowledge can sometimes be gleaned through the embodied experience of making and using that tool.

David Cronenberg is known for his squishy body horror and peculiar obsession with the wet intersection of media and human bodies. He is also one of the great (and underacknowledged) cinematic world-builders, and the many uncanny instruments and strange tools that populate his films play a significant role in building out the mise en scene. The tools make sense within the filmic worlds, where a rogue OBGYN might design a spread of “gynecological instruments for operating on mutant women,” or a gun assembled of bone and cartilage might become an essential weapon for a character in a grimy game scene. They also make sense of the filmic worlds, prompting audiences to imagine what else is going on in a culture where having a new orifice punched into your spinal column with a modified pneumatic airgun is as normal as an ear-piercing trip to Claire’s might be for us. Cronenberg’s instruments may be fake in the sense that they don’t exist outside of the film, but their narrative function is very real.

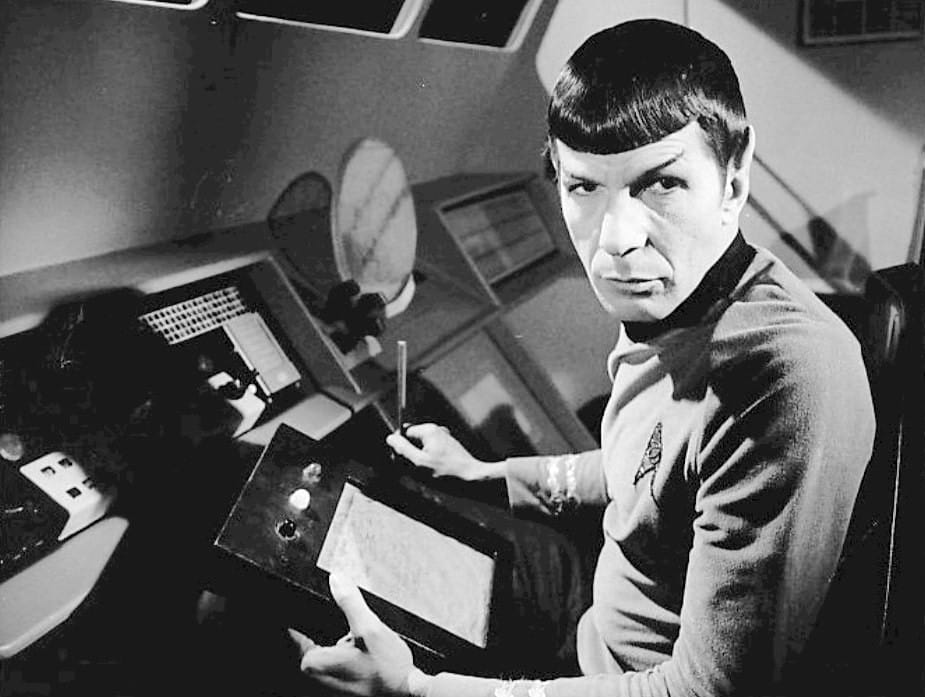

The Star Trek universe is a musical place, full of instruments and melodies that echo across the known and unknown galaxies. It is also a fantastical place. Unencumbered by Earth-bound laws of physics and sound theory, the show’s designers gave themselves freedom to imagine and create musical instruments as aesthetic reflections of the cultures in the Trek universe, from Edo harps to Taresian chimes. How did they work? Who knows! As artist and digital instrument developer Astrid Bin noticed during her pandemic-era Star Trek rewatch,

the people designing these instruments weren’t making “musical instruments” the way we know them, as functional cultural objects that produce sound of some kind. Rather, Trek instruments are storytelling devices, alluring objects that have a narrative and character function, and the sound they make and how they might work is completely secondary.

While Taylor Swift’s tailored pianos still need to produce an appealing sound even as they function as visual storytelling devices, Trek instruments have no such restrictions. During her deep dive, Bin found herself drawn to one particular instrument from The Next Generation — a mysterious Aldean instrument controlled by the thoughts and emotions of its player. She set out to create a real-world version of the instrument, pairing concepts from affective computing with technical components including grip strength sensors and an accelerometer. By the end, she had something playable.

Astrid Bin’s Aldean instrument is an example of a fake instrument that escaped on-screen containment to manifest in our real world: an alluring narrative object turned functional cultural object. She’s not alone in her desire to reverse-engineer a science fiction instrument. History is littered with examples of imaginary devices so evocative they prompted inventors to try and make them real, to varying degrees of success. On the one end, the first personal cell phone, was inspired by Captain Kirk’s communicator; on the other, Zuckerberg’s ill-fated Metaverse was inspired by Neal Stephenson's novel Snow Crash. The question is, what world do we want to bring into being with the tools we create or the imaginary instruments we realize? In other words, are we building the Torment Nexus? Or are we building the Aldean instrument?

SCOPE CREEP.

- Scientists at Loughborough University made what they believe to be (a picture of) the world’s smallest violin using nanotechnology, which is smaller than the width of a human hair.

- The that’s a booklight subreddit is a fun scroll of posts about movie and TV props which are repurposed from household and commercial items. The to-the-point captions are great, too. A couple of our favourite posts are “Bomb timer in S.W.A.T is just a TI-83 plus calculator” and “This eyepatch from Slammer (1986) is a piece of a steamer basket.”

- Aphex Twin’s performance at the Barbican — the only time we’ve seen someone swing a grand piano like a pendulum to produce the doppler effect.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to Bevan, our resident synth advisor, for sending us links and fact checking the intro.

Love, Anna and Kelly