After a few days out of the water, Yiannis Maniatakos would develop what his wife called a land-locked look in his eye. Many people love the sea, but Maniatakos went further than most. He was a painter, and his subject was the ocean floor. He made all his paintings up close and underwater.

Before painting, he would prepare a canvas with a hydrophobic coating (ingredients today unknown) to make it water-repellent. With weights tied to his ankles and wearing a breathing apparatus of his own devising, he would sink with his canvas to the ocean floor — often while a family member waited above in a sailboat — and press oil paint onto the canvas with a spatula. Back on the surface, he would wash the painting with fresh water and dry it before returning it, once more, to the sea bed to “cure.”

I saw four of these paintings last summer in the Sylvia Kouvali gallery in London. The light, craggy walls and sloped and grooved brick floors (remaining from the space’s 19th-century life as a stable) gave the room a slightly benthic feeling, a good match for the exhibit. Entering the gallery was a little like walking into an old refrigerator, or a shoebox into which someone had placed four windows to the water. Seeing the paintings, I immediately felt that I was in direct contact with the ocean.

The paintings were flat, blurry, and rough. The scenes, all burnished blue, depicted “fairly featureless shelves of sediment, at times framed by dark formless rocks and punctuated by patches of seaweed.” I could sense the forces of pressure and occlusion that let the paint adhere to the canvas instead of drifting away. In a documentary about his practice, Maniatakos said in voiceover that “the fear which is present in every seabed” drew him in like a magnet. There is some of that fear in the paintings, but there’s also an immersive calm.

This summer, a lot is underwater. New York City has been inundated with rain, and Texas is reckoning with the destruction and tragic loss of life of last month’s flash floods. China’s Guizhou province and Nigeria’s central Niger state are both dealing with the aftermath of deluge. Glacial melt in the mountainous northern region of Pakistan is threatened by a repeat of 2022’s devastation. An unease stronger than that present in Matakios’s seabed paintings, and more diffuse, pervades public and political life. Facing this unease, I am inspired by Maniatakos’s inventiveness, devotion, and persistence in returning to the scene. There is something redemptive in his process, when the canvas is cut loose from its lead weights and washed and dried in the sun. Maniatakos felt that he needed to work in this way, to do this intense, particular thing. With his own tools, and the help of his family and friends, he did it over and over again, until he was very old. The newest painting on display at Sylvia Kouvali is from 2007, when the artist was 72.

Scope of Work is supported by paying members. If you appreciate writing that explores infrastructure, devotion, and persistence—consider becoming one.

A more recent aquatic triumph: the Seine is officially swimmable for the first time in a century. This summer, the river opened three sites to the public, and Parisians beset by the late June heat dome rejoiced. The opening comes on the heels of a €1.4 billion cleanup effort that enabled the river’s role in the 2024 Paris Olympics. Bringing down the levels of dangerous bacteria in the water required the conversion or repair of some 10,000 pipes, and the construction of a combined sewer overflow tank big enough to be described as an underground cathedral.

Lacking a river to swim in, New Yorkers in heat waves have historically turned to the city’s fire hydrants for a gush of cool water. Opening a fire hydrant oneself is against the rules, but it is possible to go to a fire station in person, fill out a form, and receive a spray cap to be fitted to the hydrant by someone from the fire department. The cap reduces the flow to a manageable 25-30 gallons per minute.

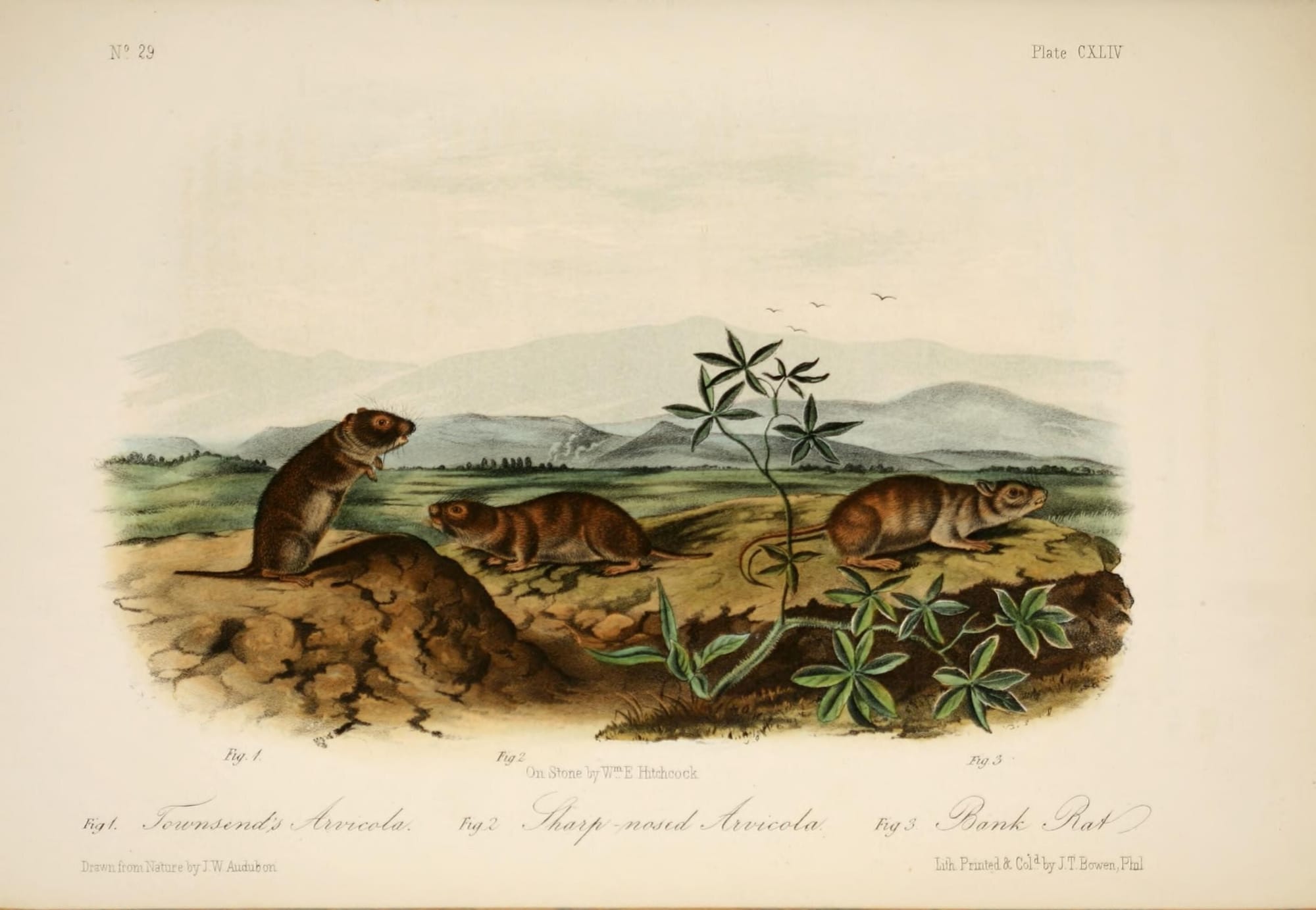

“Scurrying seafarers,” scourge of the ship-visited world, our mirror species: for centuries, rats have ridden along on the infrastructures and ecosystems of global commerce. The New York Review of Architecture has published a handful of essays invoking the rat as the mascot of the city, and examining its relationship to urban infrastructure. In 2023’s “Save Penn Station,” architecture critic Thomas de Monchaux described the rat as

the natural sigil and familiar of New York City: maritime, hungry, brave, ingenious, ambitious, unsentimental, disloyal, charismatic, sociable, adaptable, violence-capable, possessed of a nocturnal glamour and feral beauty.

In the more recent “Rat’s Amore,” full of hot takes by Aaron Timms, the rat is cast as both foil and foe to Eric Adams, as a symbol of crumbling state capacity and the failure of individualized solutions. This is where I first heard about the pneumatic sanitation system on Roosevelt Island, which “retrieves household garbage from more than 14,000 residents and sucks it through turbine-powered tubes at a speed of 70 miles per hour before depositing it in a central processing plant.”

Roosevelt Island was designed to be mostly carless, ruling out curbside pickup; thanks to its well-sealed trash tubes, the sanitation system is mostly ratless. Timms writes that the still-functioning tube system implemented in 1974 belongs

to an era when funds for public construction were far more abundant than they are today, and the state—operating through powerful agencies like the erstwhile Urban Development Corporation—had either the self-confidence to go it alone on big works or the dexterity to forge productive partnerships with private capital.

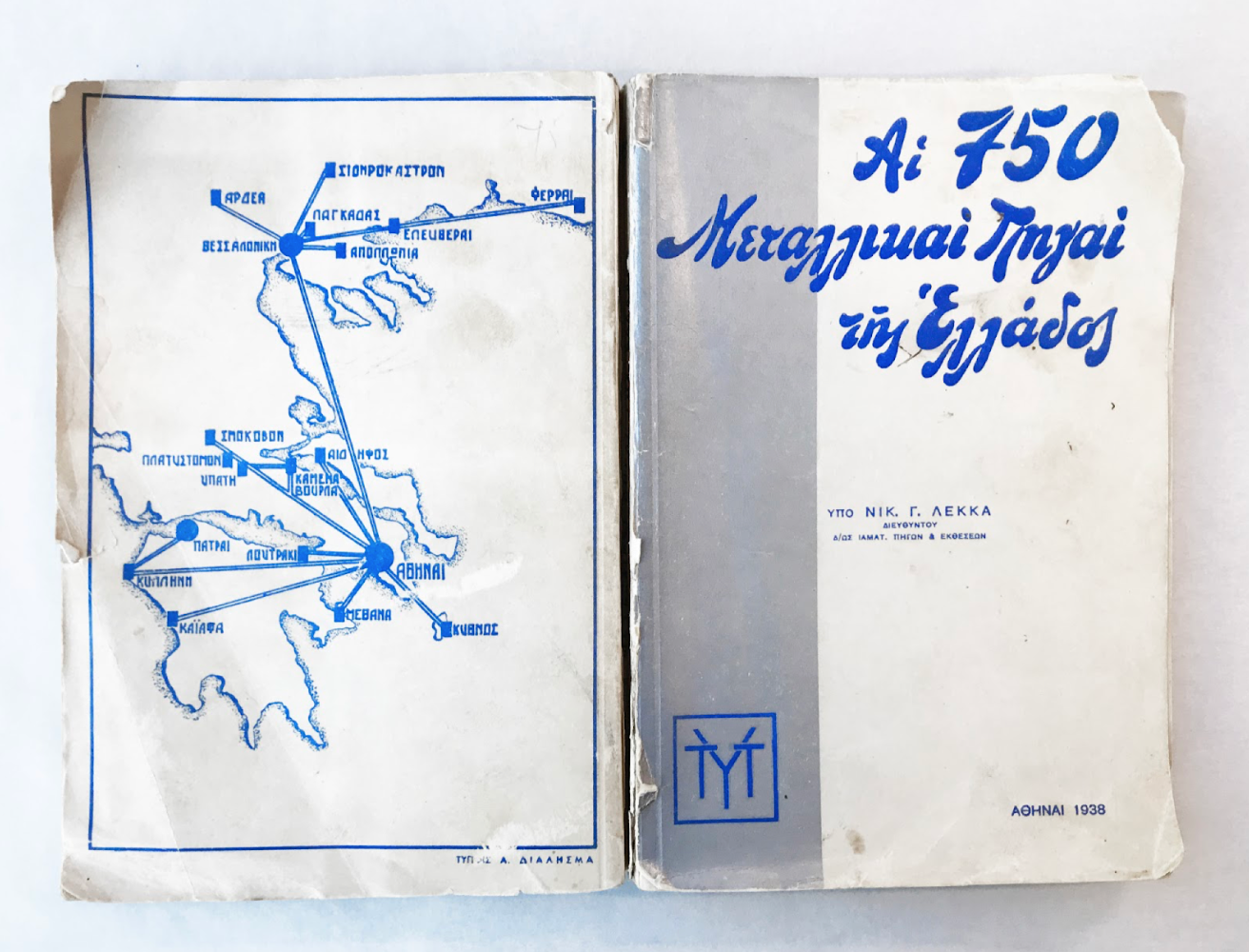

Friends of the 750 Mineral Springs of Greece is a Zurich-based association dedicated to the maintenance and recovery of mineral springs and baths. Their website offers a slightly cryptic catalog of springs–not quite the 750 described in Nikolaos Lekkas’s 1938 book The 750 Mineral Springs of Greece (“simultaneously a travel guide, geochemical cartography and medical compendium”), but enough to get one’s feet wet.

SCOPE CREEP.

The rest of today’s newsletter is available to paying members only. Join now to support thoughtful, idiosyncratic writing—and get full access to our archives.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now