A programming note, written mostly for myself: Starting this Friday I’ll be camping out for a week in southern Vermont, writing in a hammock during the mornings and middays and going on long bike rides in the afternoons. My change of venue, and the long stretches of champagne gravel I’m hoping to ride, shouldn’t disrupt production or publication of this newsletter — but if you’ve got any words of encouragement for someone gearing up for a solitary and meditative workweek, I’ll take ‘em ;)

“San-Yak,” more or less

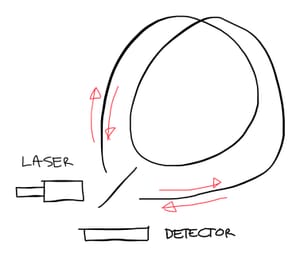

Let’s say you had a very long length of fiber optic cable — two whole kilometers’ worth, all looped onto the same reel. If you were to shine a laser into one end of the cable, it would zoom around and around the reel and pop out the other end ten microseconds later. Just to make sure you’re not crazy, you try shining the laser the other direction; again, it travels the full length of your fiber optic cable in exactly ten microseconds. This is great; the speed of light is [waves hands] constant, and it doesn’t matter whether your laser is going from one end to the other, or back again — it takes the same amount of time to do so either way.

Except! Except if your reel starts to roll. You give the reel a spin, then shine the laser into one end of the cable or the other: When light travels in the same direction as the reel rotates, the light’s fixed speed means that it takes longer to reach the other end. This is the principle behind the Sagnac (“San-Yak,” more or less) Effect, in which the same laser beam is split such that half travels around a loop one way and half travels the other way. When the two halves exit the loop they are recombined, and their waveforms can be seen to interfere in patterns determined by the loop’s rotation. By measuring their interference, you can calculate just how quickly the loop is rotating. This ends up being useful, and allows us to build fiber-optic gyroscopes — highly accurate devices, with no moving parts, that are used for inertial navigation and other applications.

It Thrives on Trash

It turns out that Sweden imports a fair amount of trash, as “its circular economy thrives on turning trash into valuable resources.” According to this analysis, 31% of Sweden’s waste is recycled, and 16% is composted (the EPA says that in total, the US recycles or composts 32.1% of its municipal solid waste). Meanwhile less than one percent of Swedish trash is landfilled; compare that to 50% of US trash. The balance — 51% of Swedish garbage — is incinerated, providing heat to a million homes and electricity to a quarter million. But Sweden’s incinerators can burn significantly more refuse than the country produces, so they regularly import more than a million tons of trash annually, mainly from the UK and Norway.

Still a Formerly Industrial Site

Bush Terminal, Sunset Park, sometime in the past. This admittedly vague image via David Wilson on Flickr.

Sunset Park sits on the harbor side of Brooklyn, the west side of the borough, maybe a twenty-minute bike ride from where I live. If Brooklyn were a face, seen in profile as it gazes towards New Jersey, then Sunset Park would run from the underside of the brow, to the deep point between the eyes (which I’m just learning is called the “nasion”), down the nasal bone until it turns into cartilage.

Among other attractions, Sunset Park has a large industrial complex on its waterfront. Originally known as Bush Terminal, the site has something like six million square feet of commercial space and is now mostly known as Industry City. Six million square feet is roughly equivalent to the playable area of a hundred and four football fields. It’s roughly a quarter the size of Prospect Park, and 48% bigger than the land that was reclaimed in the construction of Battery Park City, and equivalent to about thirty-two Walmart Supercenters. Anyway it’s a lot of space. I think my first actual trip to Industry City was in maybe 2016, when I visited a bike share startup there. They were about to release a new e-bike, the first I had seen in the US, and we took a freight elevator downstairs and rode it around outside for a while. It was the first in a string of sincerely industrial visits I took to Industry City, including: a high-end lighting manufacturer that used a piece of factory software I was trying to sell them more of; a wood shop that was jettisoning a bunch of old equipment I wanted; and in the spring of 2020 a 3D printing shop, to get freshly-made face shields that I was driving to a doctor in Nassau County. None of these trips came to very much, I’m afraid, but they were attempts: to build production capacity, to keep heavy-ish machinery running, to make useful stuff locally.

On my most recent visit to Industry City, though, my kids and I ate some ramen and then went to the chocolate shop. It was a Sunday, and the chocolate shop’s production line wasn’t working, and the whole experience had a decidedly retail flavor to it. I am not the first person to have noticed this, and in fact it’s something that some Sunset Park residents were rather up in arms about in the mid- to late-twenty-teens: a big commercial real estate manager, retreating from the idea that actual industry might occupy the ground floor of this once-active site. Industry City was being redeveloped, production space being reallocated to dining and office work.

I was vaguely aware of this fight previously, but was honestly distracted by what was going on at the Brooklyn Navy Yard (which is a little closer to where I live) and the Brooklyn Army Terminal (which is honestly a stunning piece of architecture, and which I made a brief but serious attempt at running a workshop at). So it was with great interest that I watched this very well-produced PBS documentary about Industry City. To me the story is, in the end, a tragedy: a plan rejected by the local community, a rezoning proposal withdrawn, and still a formerly industrial site gentrified. The fight came to a head in 2020, when Democratic city officials coalesced around progressive opposition to Industry City’s expansion plan. The expansion was claimed to be capable of generating twenty thousand jobs, which, who the heck knows. But even without the expansion, Industry City seems to have become less and less industrial: I have not partaken of this particular experience yet, but I’m told that the climbing gym there (which is marketed towards “families and groups”) is a great way to kill some time with elementary school-aged kids.

See It My Way

In addition to reading QED with the SOW Reading Group, I’m reading (thanks to Mike) Joan Didion’s Let Me Tell You What I Mean and listening (thanks to George) to Kim Stanley Robinson’s The High Sierra. From the Didion:

In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions—with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.

I had not thought of it this way, and it was interesting to sense Didion’s intrusion into my most private space — i.e., my feeling has often been that writing is a vulnerable act, like being on the mirrored side of a one-way mirror.

I’m not as far into The High Sierra yet, and in truth I mostly want to write about the (thematically related) book I listened to before it — William Finnegan’s Barbarian Days, which I thought was simply fantastic and which I promptly re-listened to twice after I finished it the first time. But there’s too much in that one to fit here, so instead I’ll just note that I enjoyed Kim Stanley Robinson’s realization about the “exposure” he experienced while climbing the Matterhorn:

This is what they meant in the climbing literature when they talked about exposure; now it was obvious that the exposure was to death. They had left that last part out, as being perhaps something that went without saying; it was mostly a British literature, after all. But there it was.

A Laudable Scientific Instinct

I really, really enjoyed Rivka Galchen’s “Unreasonable,” which was published in the current issue of the New Yorker (she also read it, wonderfully, on The Writer’s Voice podcast). The story is about many things — parenting, current events, office politics, bees — and the voice that Galchen uses is surprising, tender, and funny. But if I were looking for a Scope-of-Work-y hook, I would tell you about how Galchen weaves her narrator’s professional and personal thoughts into a single stream, transitioning from a touching description of her ten-year-old daughter straight into an explanation of evolutionary life history strategies:

When I pick her up from school and ask her about the wolf app, she says she will delete it. She says it right away. She doesn’t argue in favor of keeping the game. She must be relieved by this intervention. I promise, Mom, she says. O.K., I should have remembered that this girl is funny, joyful, and resilient. When she was three, and we were in the gift shop of a small zoo, I told her she could choose one stuffed animal, and she chose a plush large-mouth bass. Humans have what are termed K-selected reproductive strategies, which means: our young grow slowly, and there are few of them, they are heavily invested in by their parents, and they have a long life span. A queen bee, in contrast, will lay two thousand eggs, but there’s little attention given to any one of her young. We would usually term this an r-selected reproductive strategy—the opposite of a K-selected reproductive strategy—though more than half survive, as the larvae are fed by their older sisters. Compare this with a large-mouth bass, who lays tens of thousands of eggs, of which only a small fraction of one per cent become adults. The K and r categories are hazy, imperfect.

The story really is lovely, and feels very much as if it’s told by someone who knows “that bees have inner lives and personality and culture” but is still “trying to persuade other people to see them that way.” And its insights into our tendency to categorize things are, I think, quite poignant:

The nearness of bees, and of other things that agitate most people, calms me. My father had three daughters and he ate watermelon with slices of cheese on the porch and he said once, over watermelon, that he was very lucky to have three girls: one beautiful, one kind, and one intelligent. Classification is a laudable scientific instinct. The ways in which the labelling and sorting don’t quite work are the glory of the process, a form of inquiry through which you catch sight of your errors and then reconsider, revise, or dispose of your categories.

A pretty excellent kid/dad joke, overheard from my kids’ favorite podcast, Grimm, Grimmer, Grimmest:

Q: What happens when you lose 25% of your roof?

If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter so far, don’t leave me out in the rain. Upgrade to a paid subscription for the rest.

Read the full story

The rest of this post is for paid members only. Sign up now to read the full post — and all of Scope of Work’s other paid posts.

Sign up now