It’s been really, really nice out recently, which is something I would say in pretty much any weather, and pretty much any season. I write this a couple weeks after the official beginning of summer, and it's hot, and my weather app currently shows a chance of rain for each of the next nine days. Today’s humidity will be between seventy-five and ninety percent. I’m pretty sure it showed the same thing a week ago, and I know that the couple of weeks before and after Memorial day were similarly hot, humid, and rainy as well. It’s been the kind of summer that gives people something to gripe about — but all I can do is talk about how much I love it.

- Celtuce is a kind of lettuce that’s cultivated more for its stem than for its leaves. Popular in China and Taiwan, celtuce is harvested when it’s maybe knee-high and its stem is about as thick as a large carrot. I don’t believe I’ve ever eaten celtuce; apparently its taste is “mild but nutty.”

- Chameleons live primarily in Africa, and three of the ten chameleon species live exclusively in Madagascar. They are preyed upon mostly by birds, then by snakes.

- The New York Times visits a ship that lays subsea power transmission cables.

I live a couple blocks from Schenectady Avenue, in Brooklyn, which is named for Schenectady, New York. I pronounce both of these places (the avenue and the city for which it's named) “skin-ECK-tit-tea”. The name “Schenectady” derives from a Mohawk word ("Schau-naugh-ta-da") which meant “over the pine plains,” though its meaning was apparently reversed when it was integrated into the settlers’ vocabularies.

Now, let’s see if I can use Schenectady — a city of a little under seventy thousand people, making it the ninth-most populous city in New York — to illustrate the literary concept of synecdoche, which I pronounce “sin-ECK-doh-key”:

One of the funny things about living in New York City is how much of our critical infrastructure is controlled by the state. The best example of this is the subway, which is run by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. New York City is, of course, by far the most metropolitan of places in the Empire State, and the vast majority of the MTA’s ridership occurs within the five boroughs, but the MTA is controlled by the governor and it's ultimately responsive to the political and practical priorities of the statewide electorate. If I had a Big Idea about how the MTA might be run differently, I’d have to get buy-in from some number of upstate voters. “That’ll never fly in Schenectady,” you might say about my plan to increase fares for riders who come in from the suburbs. We might go back and forth about this, brainstorming policies that would discriminate based on a rider’s home address, and you might find yourself saying “Schenectady would never vote for” something, with “Schenectady” standing in for millions of upstate citizens, politicians, and commentators.

And you would probably be right. And, you would be using “Schenectady” as a synecdoche.

Scope of Work is made possible by readers like you. Join as a paying member today, and take 20% off in perpetuity.

They say that there’s no accounting for bad taste. Taste, here, is a synonym for judgement, or maybe aesthetic orientation. Used in this sense, taste is this weird tendency that people have — a set of preferences that are decided at random and without justification. We all taste the world differently; it’s not a deterministic process. This is in contrast to our other senses: If you see something, hear something, smell or feel something, we expect you to respond in a particular way. But if you taste it, well, all bets are off.

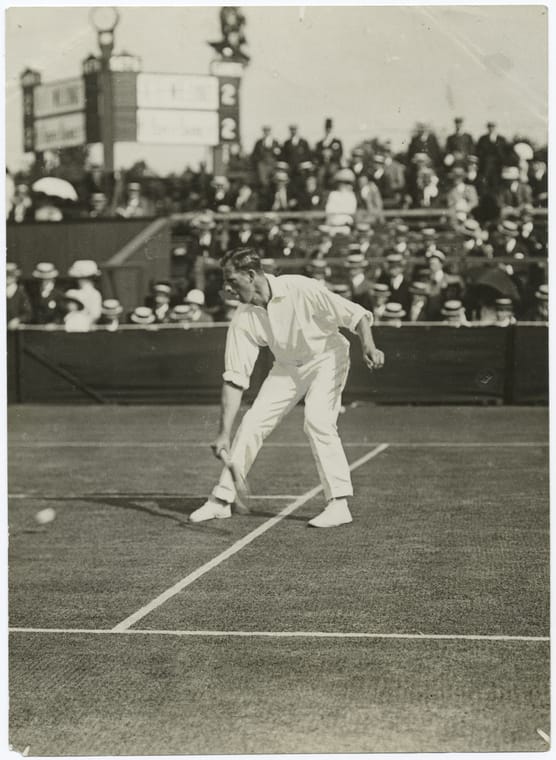

I’ve been watching Wimbledon and the Tour de France, with sides of Netflix’s Tour de France: Unchained (a.k.a. Au cœur du peloton). Combined, this is as much sports coverage as I’ve consumed in the past decade. I’ve watched on the couch, sitting in front of our old thirty-two-inch television, and I’ve watched on my laptop, and I’ve watched on my phone. I’ve watched as a primary activity, leaning in for the excitement of a good serve-volley or sprint finish, and I’ve watched in the background, letting the crowd noise and the intangible waves of tension and release wash over me as I focus on house chores and low-stakes administrative work.

The broadcast production values in these two sports could not be farther apart, and I find myself embarrassed and frustrated whenever I turn to cycling. As far as I can tell, the Tour generates a similar amount of revenue as Wimbledon does, but it’s much more reliant on sponsorships due to the fact that the event itself is held on public roads and is therefore unable to sell tickets to in-person spectators. This difference helps to explain the visual separation between the two events: While Wimbledon’s sartorial conformity makes its players look more like inmates than like athletes, cycling kits are slathered with the names and logos of dozens of corporate and municipal sponsors.

But it doesn’t stop there. In addition to their sponsors’ logos, professional cyclists are often required to wear colors and other insignia denoting the accolades they’ve achieved in the past. The Tour’s general classification leader wears yellow, and its points leader wears green, and so on; these colors give the viewer information about the current state of the twenty-one-stage race itself. But there’s a separate set of insignia for riders who’ve won their country’s most recent UCI championships (the reigning US champion, Quinn Simmons, sports a gaudy and heroic stars-and-strips jersey, which looks totally unlike his team’s yellow-and-red kit), and rainbow stripes for the world championship (big stripes across the torso for the current year’s winner, and smaller stripes on the collars and cuffs for the winners of previous years). The result is that it’s often quite difficult to identify which rider is on which team — a critical piece of information, if you’re trying to understand the complex strategies that they’re employing.

If these annoyances aren’t enough, I find Peacock’s Tour de France coverage additionally infuriating. Their extended highlight reels, which typically run around twenty-five minutes and are free to watch on YouTube, are cut from the full stage rather than being produced as standalone products. The result is that the commentary jumps all over the place, and it’s hard to tell what part of the race you’re watching at any given moment. But switch over to watching full stages, and the experience is even more frustrating. A stage takes maybe five hours to complete, with the vast majority of the broadcast being fairly dull. They also start quite early in the (US) day, so maybe you turn them on a few hours after they begin and hope to skip the less interesting parts. Luckily, you can predict beforehand what the most exciting moments are likely to be: the finish, of course, plus a handful of intermediate sprints and climbs. But here’s the rub: Peacock’s stream lacks a persistent indication of where the riders are relative to those sprints and climbs, so when you try to find them you end up just fast-forwarding to a semi-random point in the broadcast, and hoping the announcers happen to call out the distance to the next exciting part promptly.

So why am I watching?

Over the past couple of years I've become increasingly interested in being witness to someone trying hard at something. It began with the 2021 film Drive My Car, which included extended, and very intimate, scenes of actors rehearsing for a production of Uncle Vanya. Observing their vulnerability, I felt vulnerable myself. It was a feeling I had grown used to but was not fully comfortable with; I suspect I'll never be fully comfortable with it, though exercising in public (and writing about my feelings on the internet) certainly helps. I began searching for other ways to come in contact with other people's effort: I looked for effort while dining out, and in live performances of various kinds, and in the bouldering gym. I was slow, however, to come around to watching professional sports — partly because of the time investment that's often necessary, and partly because of my reflexive discomfort with mass fandom. But the more time I invest in watching sports, the more I find moments of sublime connection — with a sprinter struggling to break away from a the disorganized mass of riders rapidly approaching a checkpoint, or with a lone player desperately trying to move past a string of poor serve returns.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work's Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible.