“Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time,” began Apsley Cherry-Garrard in his memoir of Antarctic travel, The Worst Journey in the World. When I woke up early on a very cold morning in Albuquerque, and turned to my husband in bed, and said out of the blue something about the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time, I thought he would know the reference. He just looked a little startled. It was cold in our house, but not that cold, and I was happy, not having a bad time. But the frozen southern continent has long attracted metaphor, and belonging to no nation, its imaginary possibilities are available to anyone. “We all have our own White South,” wrote the explorer Ernest Shackleton, who spent more than two years stuck in the monochromatic pack ice off of the Antarctic peninsula. If that sounds too intense for you, consider Thomas Pynchon: “You wait. Everyone has an Antarctic.”

My Antarctic opened up in high school, when I read Sur by Ursula K. Le Guin, and the quiet memory of the Yelcho expedition detailed therein was stored in the snowpack of my teenage brain. In 2020, I found The South Pole: A Historical Reader at my grandparents’ house and The Noose of Laurels at Powell’s and spun into a mild obsession that peaked around minute 22 of the National Geographic documentary Survival! The Shackleton Story. Now I live part of the time near the Scott Polar Research Institute, and I can go in when I feel like it and admire the museum’s sealskin and sinew anoraks and antique scientific instruments and maybe cry a little when I get to the plaque about Lawrence Oates.

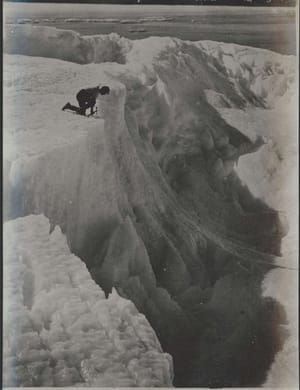

Antarctic explorers are celebrated, traditionally, for their embodiment of humane values in an impossibly harsh environment. Shackleton, in particular, came to exemplify the compassionate and pragmatic leader. When the ship Endurance was frozen, crushed, and swallowed by ice, he and navigator Frank Worsley led its crew of twenty-eight through the next nineteen months without a single casualty.

As ice melts and sea levels rise, the image of Antarctica as an inhuman place is troubled. It is a landscape at a precipice, changing shape as the sea ice shrinks, with global political and ecological significance. A quote from geologist and explorer Raymond Priestley is beloved by adventurers and self-help writers alike: “For scientific leadership, give me Scott. For swift and efficient travel, Amundsen. But when you’re in a hopeless situation, when there seems no way out, get on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” In a time of rapidly shifting conditions, polarization, and amplification of planetary extremes, when scientific leadership and swift and efficient action are also useful and necessary, I still hope for a little Shackleton.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

The scientists and support staff who live on Antarctic research bases are ensconced in a metaphorical parka of technological and logistical systems, making their day-to-day less brutal than what Shackleton’s crew endured. Underpinning their operations is an electrical infrastructure that runs primarily on aviation fuel. The blogger behind brr.fyi concludes their deep, deep dive into South Pole electrical infrastructure with the observation that the grid there is hardly different, overall, from what you’d find somewhere else in the world. Power generation, though, is a grueling and emissions-intensive affair, complicated by the low availability of hydrocarbons. The expense and effort associated with shipping in millions of gallons of fuel put the U.S. in search of alternatives as scientific operations at the McMurdo research base expanded in the fifties. In a period of nuclear optimism, a small reactor was proposed to help power McMurdo. A 1961 article describes how it was assembled from prefabricated sections, “designed to be put together and readied for full power generation within 75 days.” It operated from 1962 to 1972, but was badly flawed, retired early, and resulted in site contamination and the need for extensive remediation. The Ross Island Wind Farm, connected to the grids of McMurdo and New Zealand’s Scott Station in 2010, has been a greater success.

If you, like brr, are “a guest and a stranger in utility areas,” or you, like me, love workbooks, you might like exploring the curriculum created by the People’s Utility Commons, called How Did the Utilities End Up This Way? And What Are We Going to Do About It? The People’s Utility Commons was a project operated by isaac sevier and Maria Stamas from 2021 to 2023, which promoted the goals and framework of utility justice, premised on the belief that “a joyful, just, healthy, democratic, and resilient utility system is possible.” isaac sevier’s utility justice reading list offers a deeper way into the topic.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

Early polar explorers survived partly on pemmican, a nutrient-dense and travel-friendly food developed by indigenous North American societies long before colonization. Its name is derived from the word pimikan in the Ojibway, Cree, and Algonquian languages, and it is sometimes translated as “manufactured grease.” Pemmican consists of tallow, dried meat, and berries; a recipe in the 1967 Traditional Indian Recipes from Fort George, Quebec notes that “a piece the size of a date square is enough for a meal.” While the sample cans on display at the Polar Museum look to me like a condensed and tinned way of having a bad time, the author of the 1967 recipe says that pemmican is good with a cup of tea.

Larissa Zhou’s AMA on extraterrestrial cooking, published by Scope of Work last year, discussed the challenges of making food and sustaining people in ‘ICE’ (Isolated, Confined, and Extreme) environments. Space is her speciality, but Antarctica is a classic ICE environment. Food has been grown in space and in Antarctica, and in both settings, the nutritional and psychological benefits of fresh produce – and the warm, green microenvironments where produce is grown – are deeply appreciated.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

The ICE-ness of polar regions poses problems for the construction, operation, and maintenance of buildings. Britain’s Halley VI research station rests on hydraulic stilts (to lift it out of rising snow drifts) and on skis (in case it needs to be moved as the ice shelf beneath it shifts). The window of time during which building materials can be shipped in and put together is short; while prefabrication has struggled to take hold in the general construction industry, Antarctic research bases serve as extreme proofs of concept for prefabrication of building elements.

Meanwhile, in the Arctic, researchers and policymakers are looking to indigenous vernacular architecture for guidance in designing resource-efficient buildings suited to the polar climate. The report “Zero Arctic” is one product of this effort. In a part of the world where a chemical reaction called thaumasite sulfate attack can transform concrete into a “non-cohesive mass without any binding or load carrying capacity,” it’s wise not to neglect the traditional building practices that have enabled indigenous communities to live comfortably there for millennia.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

A Flooded Thirsty World by Rania Ghosn chronicles the travels of several icebergs, real and imaginary. It starts with the hunks of glacier transported from Greenland to Copenhagen for the 2019 IPCC (part of the artwork Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing) and ends on the hypothetical journey of a 40-million-tonne iceberg towed from Antarctica to the Hormuz Strait Dam in Saudi Arabia – an idea which was debated at a conference on “Iceberg Utilization for Freshwater Production, Weather Modification, and Other Applications” in Iowa in 1977. Ghosn examines icebergs as precarious monumental figures evoking the environmental uncanny. Antarctic icebergs are res nullius, the property of no one, Ghosn writes:

Unlike whales, uranium, and other riches regulated by the 1991 Madrid Protocol, icebergs are legally free for the taking without interference from national or regulatory bodies. Finders are keepers.

The transit of an iceberg might be camp, but the movement of cold is commonplace. As Nicola Twilley wrote in her essay The Coldscape: From the tank farm to the sushi coffin (and as I expect she’ll expand upon in Frostbite, her new book set to come out in June), most of what we eat passes through a vast network of artificially chilled transport and storage space called the cold chain, “as essential as it is overlooked.” Refrigerated shipping containers make growing food in one place and trucking it to another viable – a fundamental concept behind modern nutrition systems and culinary preferences.

The refrigerated, insulated, intermodal container is at the heart of the global food supply chain. And at the heart of the trucking industry is its workforce: a demographic marked by an annual turnover rate, at large fleets in recent years, higher than 90 percent. Emily Gogolak wanted to know who, given the notorious hardship of the long-haul lifestyle and the steep decline of truckers’ earnings since deregulation in the 1980s, was “still feeding the churn.” Her account of going to trucking school in central Texas to earn a commercial driver’s license is a textured and personal look at the economics of the industry and the lives of people in it.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

The runway at the Norwegian Polar Institute’s Troll Research Station was constructed over a period of two years, during which the blue ice it sits on (called blue because it forms from snow that has fallen on a glacier and compressed under its own weight, squeezing out the air bubbles and attaining a blue color through the resulting enlargement of ice crystals) was leveled with a laser cutter. In the lead up to a period of activity (landings and take-offs occur several times a week through the Austral summer months), the runway is cleared of snow, inspected, and repaired. After use, it is re-covered with snow to help keep it cold.

The drift, year over year, of the magnetic south pole exerts a kind of twisting force on the runway, causing it to move unevenly by a few meters per annum. Eventually, it will need to be straightened. But it’s not only in the far south that magnetic drift makes work for airport operators. From Fairbanks to Tampa, runways named and numbered in accordance with points on a magnetic compass must be relabeled every so often to reflect their changed positions relative to the Earth’s magnetic poles.

Human-made structures can also interfere with magnetic navigation. What is now London City Airport was once a shipping dock, its walls dotted with cast iron bollards and its nearby warehousing area encircled by railroads. Portions of the rail and bollards were left in place when the airport was built, along with a steel-wrapped concrete pile left over from an old oil pipeline.

In 2006, a pilot departing from London City Airport was thrown off by significant discrepancies across readings in the plane’s magnetic navigation system. Following emergency procedures, the plane switched to a different (but still magnetic) reference system, but the unreliable readings persisted, and air traffic controllers had to step in to navigate the plane back down to the airport it had just left. After the incident, a U.K. Air Accidents Investigation Branch inspector walked along the runway area with a hand-held magnetic compass, and witnessed needle deviations up to plus or minus 60 degrees. The investigation credited these to local ferrous magnetic signature anomalies: magnetic artifacts of the site’s prior use, emanating from the buried railways, bollards, and steel. It emerged that navigational confusion had been an occasional occurrence there for years, but was misattributed to pilot failure.

SCOPE CREEP.

I’ve been feeding myself wonderful short stories by Grace Paley, like this one, published in the New Yorker in 1979. Snippets and memories in them document the economic and cultural changes a city undergoes: “Vesey Street was the downtown garden center of the city when the city still had wonderful centers of commerce,” and “I passed our local bookstore, which was doing well, with ‘The Joy of All Sex’ underpinning its prosperity. The owner… was a great success. (He didn’t know that three years later his rent would be tripled, he would become a sad failure, and the landlord, feeling himself brilliant, an outwitting entrepreneur, a star in the microeconomic heavens, would be the famous success.)” Paley’s ear for the voices of characters and her committed anti-war politics are perennial inspirations to me.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to Eric Andersson and JonPaul Turner for links in the Scope of Work Slack.

Love, Natasha

p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.