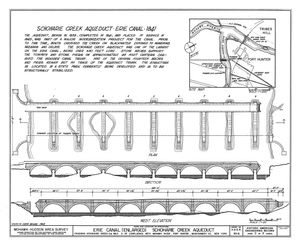

As the Historic Site Manager unlocked the gate, we signed our release forms and ambled under heavy stratus clouds onto a precarious stone bridge, becoming characters in our own Romantic scene of infrastructural ruin. Carved into a stone at the end of the dilapidated structure, just before it drops off into the Schoharie Creek below, is its mason’s mark: “Otis Eddy Bldr 1841.” This rewilded six-arch stretch is what remains of the Schoharie Aqueduct, where the Erie Canal once traversed Schoharie Creek – an aqueous bridge hovering above the natural waterway below.

Built nearly 200 years ago, the Erie Canal catalyzed industrialization and trade between the Eastern Seaboard and the Midwest, and it established New York City as the nation’s commercial capital. It also made occasion for a host of engineering advancements, from hydraulic cement to moveable dams to the founding of one of the United States’ first technical universities, the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. The Schoharie Aqueduct – large enough to allow barges to cross over and above a flood-prone river – was yet another. But the Erie Canal’s life as a piece of mass transit infrastructure was relatively short-lived. As the railroads, the interstate highways, and the St. Lawrence Seaway drained the canal’s commercial traffic, the communities built alongside the canal lost one of their main economic engines.

Today, the Schoharie Aqueduct might embody John Ruskin’s “glorious ruins”: “remnants of [a] mighty state long ago, now restored to nature’s peace.” But the system it emblematizes is still a vital piece of infrastructure. The Canal’s 565 kilometers (351 miles) carry far less cargo than they did at their peak over a century ago, but they remain an important piece of social, economic, and ecological infrastructure. In early June I visited the Eastern part of the canal system with two friends from the New York State Canal Corporation to see how the Erie Canal is being reimagined – and how the communities through which it passes are reimagining themselves, too.

-Shannon Mattern

The most clicked link from last week's issue (~12% of opens) was Alexis Madrigal on growing carrots. In the Members' Slack, the #community-shameless channel is full of incredible projects by community members, like Julian Bleecker's interview with Che-Wei Wang of CW&T and Nick Fountain's exposé on false data in behavioral economics.

SPONSORED.

Xometry, which has long been known for CNC machining and 3D printing is a great source for laser and water jet cutting as well. They’ve recently updated their sheet cutting pricing model and are doing some great work in that area. You can get an instant quote today on their site.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

Several skilled historians – among them Peter Bernstein, Gerald Koeppel, and Carol Sheriff – have documented the herculean planning and strategizing efforts that yielded the Erie Canal and led to its two-phase enlargement in 1862 and 1903. Over the past several decades, since commercial traffic has waned, responsibility for the canals’ operation and maintenance has passed through many hands. In 1992 state officials shifted control of the Canal Corporation from the New York State Department of Transportation to the Thruway Authority, and then, in 2017, to the New York Power Authority (NYPA).

These jurisdictional shifts have both reflected and transformed how the canal has been framed as a strategic asset or liability, and how officials and communities plan for its refurbishment or retreat. To NYPA, the canal is a “large scale civil asset;” it has associated revenues and expenses, and plays a small but significant role in the state’s hydroelectric generation system. At the same time, though, much of the State’s recent efforts have been directed at envisioning the canals as a “recreationway” with services and amenities for recreational boaters and fishers, waterfront parks and pavilions, and a canalway trail.

As NYPA assumed responsibility for the canals, it launched the Reimagine the Canals Competition, which noted the canal’s “untapped potential as an economic asset, for both tourism and recreational uses.” Two years later, then-governor Andrew Cuomo convened a Reimagine the Canals Task Force to “determine how this historic infrastructure asset can be mobilized anew to promote the health and well-being of upstate New York’s communities, economies, and ecosystems.” Its report, published in early 2020, acknowledged “the shift from commercial to recreational use,” the high costs of maintaining the canal ($140M in 2019), and the fact that the canal passes through some of New York State’s “most disadvantaged communities.” Yet its closing section distinguishes the canal system from a ruin: “In contrast to the silent mills, crumbling dams, and remnants of canals that can today be found in post-industrial towns across America, the Erie Canal offers something wholly unique: it is still functioning.”

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

The canal was engineered as a massive aqueous engine and conduit for making and manufacturing. “By bringing the interior to the seas and the seas into the interior,” Peter Bernstein writes in Wedding of the Waters, “the Erie Canal would shape a great nation, knit the sinews of the Industrial Revolution, propel globalization – extending America’s networks outside our own borders – and revolutionize the production and supply of food for the entire world. That was by no means all. In time, this skinny ditch in upstate New York would demonstrate that trade and commerce are the keys to the expansion of prosperity and freedom itself.”

Let’s consider its impact on just two upstate communities. Bernstein writes: “Forty miles east of Utica, Canajoharie was known for its very popular footraces in the early days of the Erie Canal, but the canal’s transportation facilities would convert the town into a large manufacturing center based on the headquarters of the Beech-Nut Company, a chewing-gum and candy firm. Farther along the Mohawk valley, there is a village originally known as Remington’s Corners [now Ilion, NY] in honor of Eliphalet Remington, the inventor of both the Remington rifle and the Remington typewriter. In 1828, Remington took advantage of the town’s location on the canal to develop global markets for his remarkable and highly successful inventions.”

While Beech-Nut is still making baby food in nearby Amsterdam, Remington's industrial legacy lives mostly as historical artifacts, some of which we found at the Herkimer Historical Society. As manufacturing facilities all along the canal have either closed up or moved to other parts of the world, much of the corridor's economy is driven by health care, higher education, leisure, and hospitality. Still, the canal provides vital resources – including spaces for recreation and education – that support these industries.

Consider Little Falls, a former hub of cheese and textile production whose population has fallen by two-thirds over the past century. As part of its Iconic Lighting Program, the Canal Corporation has illuminated Lock E-17, highlighting the canal as a source of civic pride and a recreational asset. They’ve also commissioned a connector bridge that will link Little Falls’ downtown to the Empire State Trail, a popular bike path across the canal. The connector is itself the hub of a larger suite of infrastructural improvements: a new bicycle and pedestrian waterfront path, a new kayak launch, and new landscaping.

Similar projects are in process all along the canal, along with cultural programming that aims to appreciate the canal’s history while acknowledging the region’s needs going forward. There’s a research fellow developing more critical and inclusive means of sharing the canal’s history; an artist in residence engaged in a “year-long creative inquiry into the Canal and the logistics of Canal maintenance and operations;” an upcoming arts triennial for the city of Medina, near Niagara Falls.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

Article 15, Section 1 of the New York State Constitution stipulates that the Erie Canal, the Oswego Canal, the Champlain Canal, and the Cayuga and Seneca Canals, and the terminals of the barge canal system “shall remain the property of the state and under its management and control forever.” If the State of New York is obligated to maintain its canals in perpetuity, it’s wise to consider what, exactly, it’s managing and controlling: not the commercial transportation infrastructure the canals were originally designed to be, but, rather, a social, economic, and environmental infrastructure.

During our June canal tour, we stopped by a couple maintenance shops, where it became clear that one of the Canal Corporation’s primary obligations and challenges is maintaining its maintainers. At Fonda, management enticed a recently retired electrician back into service so she could train new staff in the bespoke arts of maintaining a century-old electric system. At Waterford, we met John, who exemplified the potential for innovation and care in the maintenance of heavy machinery and massive systems – and the teams responsible for that work. John’s team is experimenting with new equipment, new polymers, and new techniques for removing the massive gaits for repair – a task typically undertaken in the winter months, when the canal is drained to facilitate maintenance. In John’s shop we observe the convergence of a 200-year-old system, 100-year-old tools, new material science, and advanced computational fabrication – an anachronistic entanglement that requires a great deal of kludging and improvisation. For instance, the canal’s locks run on direct current (DC) power, but DC generators are hard to come by – so the shop has engineered their own.

Many of the folks we met on these shop floors are multi-generational state-employed tradesmen. John started his career in the private sector, but he’s chosen to stay with the Canal Corporation, he told us, because there’s always an opportunity, a necessity, to innovate when you’re working with a system for which there are no readily available replacement parts. “You can’t sub out here,” he told us. In other words, there are no sub-contractors who could do this work. The system’s continual operation depends upon the folks in that cavernous shop – and their counterparts at other facilities across the state.

Yet the maintenance of the Canal System as something more than a mechanical operation – as a social and economic infrastructure, as a critical artery within regional ecosystems, as a conduit for cultural production – requires the investment and expertise of a much larger maintenance team encompassing designers, historians, community organizers, and more. And while some of those experts might not face the same material limitations confronting the canals’ tradespeople, they would all do well to acknowledge the resourcefulness and creativity in the system’s repair shops.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

Roughly 4.1 million metric tons (4.6 million tons) of freight floated along the canal in 1880. By 2022, that number had dropped to 4500. A decade ago the State considered the possibility of promoting inland waterborne containerized freight like we see in Europe, but more recent efforts have focused on the canal as a different kind of logistical system: one that distributes economic and recreational opportunity. Leisure boaters – from local kayakers to long-haul “loopers,” who glide up the Atlantic coast, across the canal, through the Great Lakes, down the Mississippi, and into the Gulf of Mexico – can pass through the canal’s locks free of charge. The Canal Corporation once exacted a fee but determined that the infrastructure to process payments cost more than the revenue they collected. But this may change in the future: Angelyn Chandler, of Reimagine the Canals, tells me that the Corporation is developing an app, like an E-ZPass for watercraft, to smooth the financial logistics undergirding the locks’ operation.

SCOPE CREEP.

“Infrastructure” has taken on new resonance and urgency in academic, artistic, and policy arenas. Consequently, its denotations have multiplied, transforming the term into a confusingly elastic concept. “Infrastructure” encompasses the technical, the political, the economic, the historical, the social, and the cultural. Roads and pipes are infrastructure, but so are protocols and care networks. If New York State has an obligation to maintain its locks, dams, and bridges, what about the communities and culture that have grown up around, and still identify with, them?

Despite the conceptual complexity, these capacious definitions of infrastructure help us appreciate what’s at stake when we decide to maintain something – or neglect it. The enormity of the Canal Corporation’s mission might also prompt us to wonder: what shouldn’t be maintained? What might be best served by permitting “graceful degradation” or “managed retreat”? How do we allocate limited resources? Where might ruination, as we saw at Schoharie Creek, serve to revitalize a holistic system?

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to the Canal Corporation’s Angelyn Chandler, Justine Heilner, and Rebecca Hughes, and to my travel companions Andy and Inge.

Love, Shannon

p.s. - For announcements on canal-related programming and recreational activities, sign up for the On the Canals newsletter!

p.p.s. - The Canal Corporation and the Erie Canal Museum are seeking applications for three 2024 lens-based artists-in-residence! Apply by September 10, 2023.

p.p.p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.