In his 1975 memoir The Periodic Table, Primo Levi recounts a brief anecdote about a mysterious slice of onion in a recipe for oil varnish. Levi, an Italian-Jewish writer, chemist, Holocaust survivor, and anti-Fascist, was working in a paint factory after the war. He came across a varnish formula, published in 1942, that included two slices of onion added to the boiling linseed oil near the end of the process. Why onion? After talking to a mentor, he learned that in the days before thermometers were common, slices of raw onion were used to gauge the temperature of the oil. The onion remained in the recipe long after its usefulness had ended, and “what had been a crude measuring operation had lost its significance and was transformed into a mysterious and magical practice.”

“The onion in the varnish” has since become a popular metaphor among computer scientists, entrepreneurs, and rationalist types – a shorthand for the importance of eliminating inessential elements that creep into a process. However, that’s not exactly what Levi describes, and it isn’t the moral of his story. His onion anecdote is told in the context of a longer conversation about the ways an ancient process like varnish manufacturing “retains in its crannies … rudiments of customs and procedures abandoned for a long time now.” This accretion isn’t a liability or a problem per se, but rather an inevitability as processes and cultures evolve over a long duration. Seemingly-insignificant events and historical accidents impact the world in unexpected ways, sometimes as much as well-laid strategies and efficient plans. Levi himself avoided being marched from Auschwitz to a second death camp due to a random (but in retrospect fortuitous) illness – an accident of history that became essential to his survival.

We have been thinking about vestigial onion slices – the secret recipes, the superstition, and the myths embedded in what we call “innovation.” Sometimes the onion can be removed. Other times a recipe evolves in the presence of an unnecessary onion slice, and omitting the onion destroys the balance. Or maybe the mythos of the onion makes for a valuable story, a boon for the varnish sellers. Either way, you can’t unbundle history without making a mess.

-Kelly & Anna Pendergrast

In the Members' Slack, our new #tangents-food channel is full of delicious conversations: homemade hot sauce tips, brewing Umeshu, and some pickle-related trade secret drama.

SPONSORED.

PulPac is on a mission to replace more than one million tons of plastic by 2025 with its ground-breaking Dry Molded Fiber manufacturing technology — the first dry industrial method that can convert cellulose fibers into packaging. Learn more about the company’s business model, how the team developed this technology and how it plans to displace plastic over time.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

Secret ingredients aren’t just marketing – trade secrets that give companies a competitive advantage can be legally protected. Unlike other intellectual property protections like patents, which provide protection only through public disclosure, the “secret” part of the trade secret is central to its legal status. Trade secrets have advantages that patents can’t provide – assuming they can in fact be kept secret, they can provide protection for an unlimited time, whereas patents eventually expire.

To qualify as a trade secret, companies must ensure the information is known only to a limited group of people, and should use precautions like confidentiality agreements to keep the secret protected – or avoid sharing the full information with anyone at all. The Uniform Trade Secrets Act was introduced in 1979 to bring consistency to state laws governing trade secrets and has since been adopted by most states. The newer Defend Trade Secrets Act came into effect in 2016, providing legal recourse through the federal court for circumstances where trade secrets are misappropriated by another party. However even trade secrets have limits, and there’s nothing stopping competitors from trying to reverse-engineer the secret themselves.

The formula for WD-40 was a trade secret for years. While the product was eventually reverse-engineered, the trade secret has stayed on as part of company lore and the handwritten formula has been treated accordingly. For example, the full formula has only been removed from a bank vault a few times, including for the 50th anniversary of the product. For this event, CEO Garry Ridge carried the formula while riding on a horse into Times Square dressed in chainmail. The WD-40 story illustrates some of the recurring tropes we found in the trade secret world: handwritten recipes, performative security, and self-perpetuated company lore.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

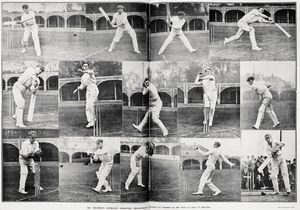

- In cricket, the condition of the ball makes a big difference to how it travels through the air. Players are allowed to polish the ball on their clothing, but other methods of altering its surface is a rule-breaking offense and is taken very seriously. The construction of the balls themselves is also key to cricket’s mystique. The cricket balls favored by the English national team are handmade for Dukes, a storied brand that traces its history back to 1760. This article tells the surprising backstory of the lacquer used to finish their legendary balls.

Back in the 1970s, Dilip Jajodia, the current owner of Dukes parent company, had been unhappy with the poor quality finish of most balls. That is, until he tried an excellent refinishing lacquer he found advertised in a cricket magazine’s classified section. This lacquer was created by Walter, a German Jew and leather expert who survived Auschwitz and moved to England after the war. Walter made the lacquer in a small room at the back of a metal engineering factory in Derbyshire on behalf of the factory owner (and cricket fanatic) Barry. This chance connection to Walter’s secret lacquer became a key part of Dilip’s career and Dukes’ mystique. When Walter died, Barry passed on the envelope containing the secret recipe to Dilip, who has protected it ever since.

To this day, Dukes’ entire operation is paper-based and Dilip continues to handmix the lacquer himself, not trusting any mass manufacturer to keep the secret. Mass manufacture would also likely disturb the aura of the entire enterprise. Dilip cites “the secret, the mystery, the romance of making cricket balls” as one of the big pleasures of his career. - Cymbal makers Zildjian and Sabian (founded by one of the Zildjian brothers after a family falling out) purport that the secret to their instruments’ iconic sound is in the process of creating a durable copper and tin alloy. Zildjian's first cymbals were produced in 1623, and according to company lore, the special process was discovered by an alchemist ancestor who worked on the outskirts of Constantinople. The secret recipe is handed down orally between generations and is protected by a high level of security. However, there is some outside debate about whether there actually is any actual secret to the alloy – and what is a trade secret without a secret? However, as historian David Shayt writes, “The long-standing faith of the cymbal-using community in the ‘Zildjian sound’ testifies to the care with which one family has nurtured its product, linking a mythic past with state-of-the-art sound innovations.” That is, trade secrets require believers, and people believe in Zildjian and Sabian.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

- Artisan-made solid ink sticks from Japanese producers like Kobaien are eye-wateringly expensive, and can fetch $1000 USD or more for a 200-gram block of ink. At this price, you’re paying for 400 years of history and tradition, and you’re also paying for an incredibly labor- and time-intensive process. If you haven’t given much thought to ink production (and why would you), this video outlines Kobaien’s method. Artisans light 400 lidded oil lamps and maintain the flames, catching smoke in the lids and collecting the resulting soot to make the ink’s pigment. None of this is a secret, but the artisans’ embodied technique and four centuries of patina on the equipment contribute to a specific way-of-making that is unlikely to be reproducible outside these historic conditions.

- A few years back, the 1970s Marantz receiver at the center of Kelly’s partner’s stereo setup stopped working properly. Not ready to give it up, he tracked down Gene of Gene’s Sound Service. Gene is one of the fewer and fewer Bay Area experts with a deep knowledge of stereo components, who could find and fix a shorted receiver or worn out belt and would even do a house call. He spent four hours working on the receiver, finally locating and fixing a broken resister. This work can be very time intensive, but his flat fee made it affordable and compelling to fix your beloved gear. As this generation of technicians retires from the trade due to age or economic imperatives (Gene himself no longer does house calls), the list of local repair services is dwindling, making it increasingly challenging to keep old equipment in good working order. Stereo repair techniques are not a secret, but specialist knowledge may be lost without practitioners passing on skills and techniques.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

- Aquavit, the Norwegian potato-based spirit infused with spices, has been around since the 1600s. Linje (“line”) aquavits are particularly famed, with a point-of-difference one of its producers has referred to as “modern sorcery”: the spirit matures in oak barrels on a four month journey at sea, crossing the equator twice in the process, before being bottled. The ocean voyage makes for a great story and is also credited for the spirit’s unique flavor. The maturation method traces back to 1805 when Norwegian ship owner Catharina Lysholm took barrels of aquavit to what was then known as the East Indies. None of the liquor was sold, so it was sent back to Norway, where upon arrival it was found to have a much better taste than when it left two years prior. Lysholm’s nephew eventually turned this story and production method into a brand, launching the Linie brand in 1821. According to some accounts, despite best efforts, the flavor profile of the sea-aged spirit has yet to be replicated in a factory setting.

- When Chicago’s Vienna Sausage Company moved from its original premises which were “put together in a Rube Goldberg kind of arrangement” to a brand new state-of-the-art facility, the sausages didn’t taste as good. For a year and a half, the company tried to work out the problem to no avail. One day, workers were reminiscing about an ex-employee, Irving, who didn’t come to work at the new factory due to the long commute required. Irving’s job was to move the sausages from the filling room to the smokehouse, taking them on a half hour journey through a maze of rooms where other products were getting produced. After noting this absence, it clicked that Irving’s daily trip was the secret ingredient – on his journey the sausages were getting pre-cooked and infused with flavor. The company was eventually able to recreate the sausages’ original taste, building a brand new room onto the factory which emulated the properties of Irving’s trip.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

In this Hacker News thread, the “onion in the varnish” lesson is interrogated and unpacked in ways that far exceed the original story. The thread unspools in ways that are instructive and features software and semiconductor engineers wrangling with the problem of maintaining or streamlining complex processes. One user notes that removing elements from a working system can be risky, because “the longer the onions have been in the recipe, the longer the recipe has evolved in the presence of onions.” Others cite the importance of documentation: “I think the moral of the story for programmers should be: If you're putting something in your code that looks like a vegetable, please put a comment on it. Ten months down the road you won't remember why that silly looking hack is there and neither will anyone else.”

SCOPE CREEP.

- Sometimes it turns out that secret family recipes aren’t so secret and in fact, are from the back of a jar or packet.

- A wall of lava lamps in San Francisco is used to encrypt the internet.

- The Beth’s song ‘Expert in a Dying Field’ is about the deep, esoteric knowledge about a person you’re left with when a relationship ends. The music video takes a more literal interpretation of the title – we see the band surrounded by an array of aging electronics and other miscellany, some of which are being repaired by a guy that reminds us a bit of Gene the stereo technician.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Members and Supporters for making this newsletter possible. Thanks also to members of the Scope of Work Slack – TW, James, Andrew, Sam, Alex, Adam, and George – for their really helpful ideas and input as we developed the idea for this newsletter. And thanks to Bevan for giving Anna a crash course in cricket ball tampering, and Brian for caring about vintage stereo equipment.

Love, Anna,Kelly

p.s. - We’d love to hear about any other trade secrets or esoteric production methods you know about. You can email us at hello@antistaticpartners.com.

p.p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here’s what we’re doing about it.