In early 2006, in an act I now see as deeply irresponsible, I drove a white Ford F-250 from the easternmost to almost the westernmost point of Interstate 80, crossing nearly the entire width of the United States. I had just graduated from college with a degree in linguistics. My focus had been in English syntax; the obvious career path was in academia, the clever one would have been computer science. But I wanted to build something, and for some reason I thought I would need this particular pickup truck to do so.

I spent the next two years living in Truckee, California, a ski town just north of Lake Tahoe, performing a gut renovation of a 50-year-old ski condo. I was largely unprepared for the experience. At the time I had spent less than a full year of my life working in construction, split across various summer vacations and gap semesters. And while I had a decent mix of physical and managerial skills (for a twenty-three-year-old), the reality is that my main qualifying traits were my relationship with the clients (my parents) and my eagerness for the challenge.

I haven’t really maintained a résumé for the past few years, but when I did, I struggled to integrate these first two years after college into any broader career narrative. But the experiences I had there have played a big role in the way I understand the built world, and I’ve increasingly come to see them as part of a larger parable – about the structure of the residential construction industry; about the perils of project management; about the naïveté of someone in their early twenties. And while I’m not sure what the parable’s ultimate point is, I do think that a few of the things I did in 2006 and 2007 deserve being written down.

PLANNING & STRATEGY.

In retrospect it’s a rather obvious observation, but the project crystallized my understanding of what a contractor does: they execute contracts. More than technical proficiency as a carpenter, or knowledge of construction and homebuilding more broadly, I needed to understand – and then execute – the work that I had committed to.

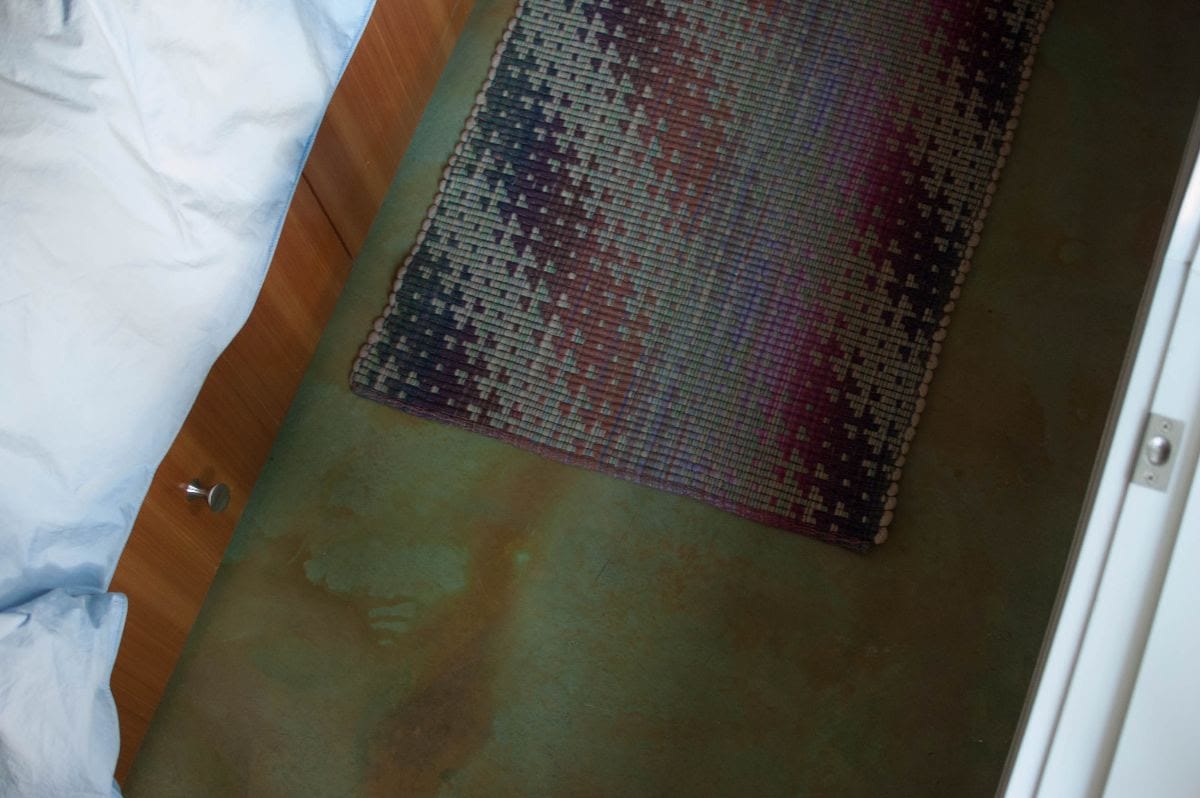

The project was supposed to be a blitz – done in about twelve months. The condo would be snowbound until late in the spring, and I wanted to be done with any big deliveries and outdoor work around Thanksgiving. In retrospect, I’m not certain whether this plan was based on any particular knowledge about the condition of the building. In order to understand a renovation’s scope of work you need to understand the condition of the building, and in order to understand the building you need to start poking holes in the walls, and nobody wants to do that until the furniture has all been moved out and the project’s clock is officially ticking. And anyway, you often can’t uncover the real disasters – the rot, the dangerously hacky old remodel work, the way one condo’s utilities are intertwined with its neighbors – until a few months into a project.

Of course I found these things, and I could sit here today and credibly explain to you how they caused the project to take two years instead of one. But the reality is that to the extent that I had a plan for how the project would go, my plan also kind of sucked. I didn’t understand the building; I didn’t understand the local construction industry; I didn’t understand how plumbing vents needed to be laid out. But most importantly, I didn’t understand how to manage my own reaction when the project didn’t go the way I had expected it to.

MAKING & MANUFACTURING.

I have considerably stronger memories about what it was like to manage the project than I do about the physical labor it involved. I spent months demolishing and rebuilding the southwestern corner of the building, which had been damaged by water infiltration from the deck structure. I built extensive shoring walls to keep the building upright while I replaced load-bearing walls, posts, and concrete. I spent weeks – months? – working on scaffolding, framing new rough openings and replacing not only the decking material but much of its structure. I can remember each of these tasks only vaguely.

Managing subcontractors (my plumber in particular, but also a tile installer that I took pleasure in firing) caused me considerable distress, and if there’s one piece of advice I’d give to twenty-three-year-old me it would be to fire the plumber. But I very much enjoyed my painter (who scoffed at the idea of painter’s tape: “if you can’t cut in an edge, you’re not on the team”), and my electrician (a lovably enthusiastic basketball nerd).

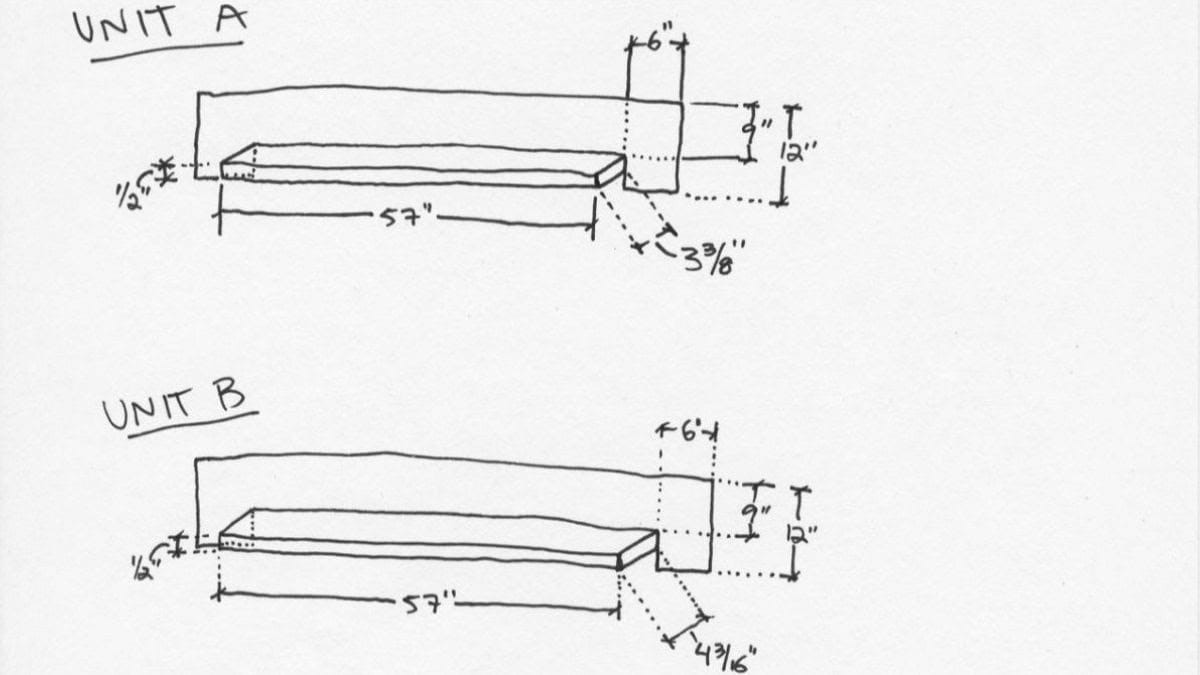

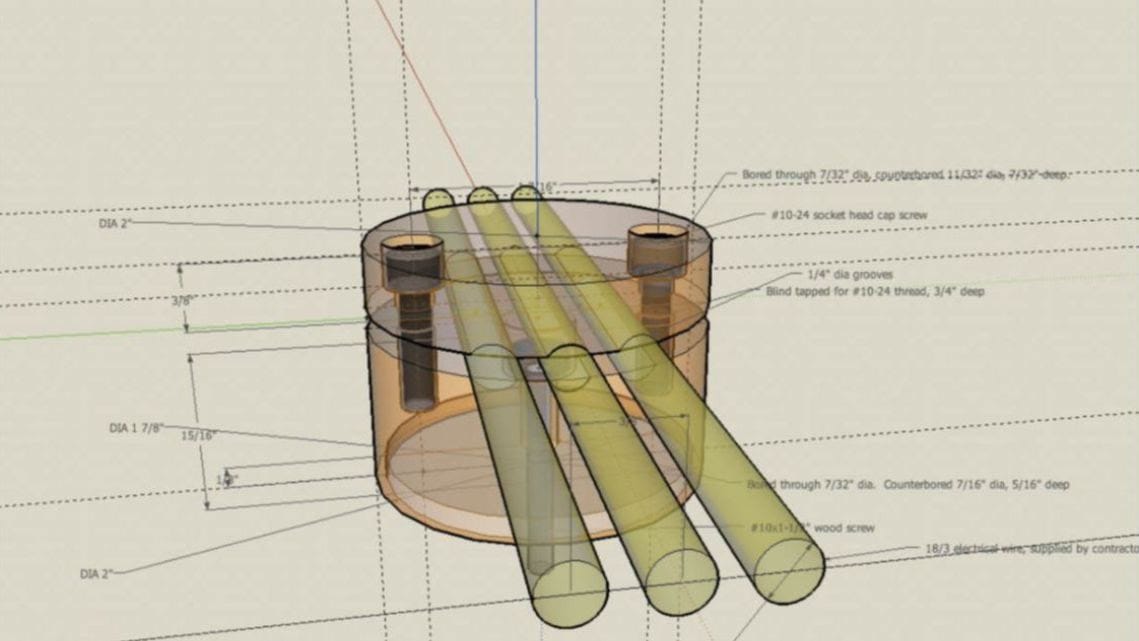

Aside from the physical labor – which I really did enjoy, whether I can recall it or not – my favorite part about the project was sourcing custom fabricated metal parts. I found a CNC shop in Sacramento to make a dozen cylindrical stainless steel wire standoffs, sending them screenshots from Sketchup as documentation. I did the same with a rather complex chimney protector, which was required to keep the crushing snow loads (nearby Donner Pass is supposedly the fourth snowiest place in the United States) from shearing the chimney right off the roof. I documented window caps and pans with paper and pencil, sending them out to a sheet metal shop in Reno to be bent, TIG welded and soldered out of stainless steel. Each of these came out wonderfully, and it was empowering and exciting to know that I could dream something up, draw it down, and have it made in a matter of weeks. I kind of can’t believe that any of them worked.

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR & OPERATIONS.

Imagine that a water main comes into your house from the street. There’s no shutoff valve on it – the pipe just comes in and starts feeding your (and your neighbor’s) water heater and faucets and appliances. You’re renovating, so you tear out your bathrooms and your kitchens and want to re-pipe everything, but you don’t have access to a shutoff valve on the street (nobody seems to really know where it is, actually), and you can’t exactly start cutting pipes when the whole thing is pressurized.

It turns out that there’s a tool for this – a pipe-freezing kit. My plumber had one, and was eager to use it for the first time on a job. The kit has a bunch of couplings that snap over the pressurized pipe, and the couplings get hooked up to a bit of tubing that runs back to a bottle of liquid carbon dioxide, and when you open the valve on the CO2, it flows out to the coupling and freezes the water inside of your main, making a nice little ice plug that lets you cut the pipe downstream and install your new shutoff valve. It’s quite clever!

If it’s your plumber’s first time using a pipe-freezing kit, and if they’re feeling a little clever themselves, they might even use two of these couplings in a row – you know, for backup. But make sure they read the instructions, because as the plugs freeze they expand outwards. This is fine if the two plugs are far enough apart, but if they’re close together then the pipe between them can burst. And if that happens, then your plumber is going to need to work quickly.

I suppose the upside of this very non-hypothetical situation was that my plumber worked quickly. But the downside was that they worked haphazardly, and a few minutes later a plug of ice rocketed across the jobsite, and behind it was many swimming pools worth of water. I can still feel the stress of that moment – the confusion about what had actually happened, the very real concern that someone might have been seriously injured, the frantic scramble to track down someone who actually did know where the water main shutoff was. It took hours; everything got wet; I’m sure I seemed shell-shocked; my plumber left the jobsite without acknowledging his mistake and still I failed to fire him.

DISTRIBUTION & LOGISTICS.

It’s an odd thing to reminisce about, but one of my favorite memories about the project was chipping up the old first floor slab and hauling all the rubble outside, up a hill, and into a dumpster. This would have been a few months into the job, and I was beginning to really understand what I was in for, and in all of the broader uncertainty it was comforting to be getting closer to the finish line one wheelbarrow at a time. It was also tough work, and I didn’t understand just how much easier it would be with a pneumatic jackhammer, and when I look back this is probably around the time that I started really enjoying drinking a beer or two after work every day.

I had biked almost every day while I was in college, but got out of the habit when I started this project. A pickup truck felt like a strong cultural identifier on construction sites, and they are indeed quite useful in hauling materials around, but I wish that I had been more willing to play the weirdo and ride my bike in. It would have been a fantastic workout – it was just ten kilometers, but included a fairly intense 300-meter climb. But for most of the project I didn’t own a road bike, and anyway the route (which, coincidentally, was the exact same one that the Donner Party was trying to take in the winter of 1846) is snowed over or at least messy for a large part of the year.

Regardless, I wish I had been more conscious of how my desire to fit in – with the pickup truck, but with other things too – affected the project. I wanted my leadership role to seem natural, and was uneasy about coming across like what I was: a recent college graduate, and a liberal, and kind of a bike weirdo. So I mostly avoided those things, and nodded along when people said things that I found dubious, and was more likely to google a technical term after the fact than to just ask what it meant in conversation. These were mistakes, and I recognize now that I’m at my best when I’m both doing a little manual labor and getting regular recreational exercise.

INSPECTION, TESTING & ANALYSIS.

Over the two summers I spent on the project, the jobsite was generally fairly busy. Most days I had two other people working with me. They were general jobsite hands – guys who worked ski patrol in the winter and would either swat nails, fight fires, or go on extreme backcountry adventures in the non-snowy months. About half of the time a subcontractor would be on site with us – a plumber, an electrician, a mason or flooring installer or finish carpenter.

But in the winters I spent long periods of time working alone. The first winter I did demolition, tearing out appliances and finishes and partition walls and trying to plan out the meat of the project. By the time the second winter came around, though, I had a better idea of what I was up against (too much!) and needed to make (extensive) structural repairs. I distinctly recall framing the staircase, which includes two landings per flight and is only supported on one side. At the time I don’t believe I had ever framed a staircase before, and I’m sure that I spent a week measuring, sketching, and eventually planning my approach.

When I think about it now, it’s as if I’m in a dream. It’s all palpable: the technical challenge at hand; the other open workstreams that I need to keep in mind; my own lack of experience; the knowledge that most of my energy is being spent on things that nobody will ever notice or understand. This last thing stands out – the more I worked alone, the more it felt as if my work was happening inside of a black hole, frozen outside of time for me and invisible to everyone else. It wasn’t so much lonely as it was existentially frightening, like maybe if nobody else witnessed my work then it wouldn’t exist at all.

When the project was finished, I packed my life up and drove back to the east coast. I had lived in California for about six years – four years for college, two years for this project – and missed the summer thunderstorms and egg sandwiches that I had grown up with. I have returned to the condo only a few times in the intervening fifteen years, and every time I visit I am flooded with memories and feelings. I learned too much there; the mistakes I made are too vivid; the way the project eventually clicked into place is too perfect. I get immense pleasure from being there. I can obsess over nearly every detail in sight.

SCOPE CREEP.

My music taste was fairly eclectic at the time when I took this project on, and I was unabashed in my willingness to blast weird stuff on the jobsite stereo. At the time I was particularly into Sun Kil Moon and the expansive work of Madlib and Jay Dilla, but I have distinct memories of playing (and receiving feedback on) everything from Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way to The Mars Volta’s De-Loused in the Comatorium.

These were the days where wearing headphones on a jobsite was still pretty rare; the iPhone wasn’t released until halfway through the project, and its penetration into my corner of the construction industry wasn’t exactly rapid. Most small jobsites would have a single boombox, locked onto a single classic rock station. But to me it was the era of the iPod Nano and OiNK.cd and the first podcasts, and so I both modernized and dominated over the auditory mood. I was young, and I was yearning for something, and at a time in which I felt disconnected from everyone around me, it was helpful to have a piece of music to drown the whole site in.

Thanks as always to Scope of Work’s Community Members for supporting this newsletter. Thanks also to everyone who I have told about how I "grew up on jobsites," a description that's vague and overly mystical, and to everyone I imposed Leo Kottke and Diane Rehm on via the jobsite stereo in 2006-2007.

Love, Spencer

p.s. - We should be better friends. Send me a note - coffee's on me :)

p.p.s. - We care about inclusivity. Here's what we're doing about it.

p.p.p.s. - We're always looking for interesting links. Send them here.